At a conference welcome reception last fall in Canada, I stepped in to join a conversation in progress. The room was full of people I did not know, so I chose a group where there was one person I had met a few hours ago, and three others new to me. I did not interject and interrupt and overstep the unwritten rules for a new arrival; I waited for a sign that I would be welcome. The person I knew, gave me a quick nod and (appropriately) continued to speak in the conversation already underway. The others did not look at me, not even a glance. I thought to myself, “my, this is strange, to not acknowledge the arrival of a newcomer to a conversation at a welcome reception.” I discerned that it was not a private conversation and made the decision to not insert myself further and conduct a little experiment: how long would they continue to not acknowledge, let alone welcome, the presence of a newcomer?

I stood and listened, observing. I waited about 10 minutes then moved away to release the experiment. I allowed time for the conversation to shift and adjust, change its focus, find those moments of transition to bring in the newcomer. They did not do it. For 10 minutes they chose to not acknowledge the presence of a newcomer, let alone welcome and weave in the newcomer.

How long would they continue to not acknowledge, let alone welcome, the presence of a newcomer?

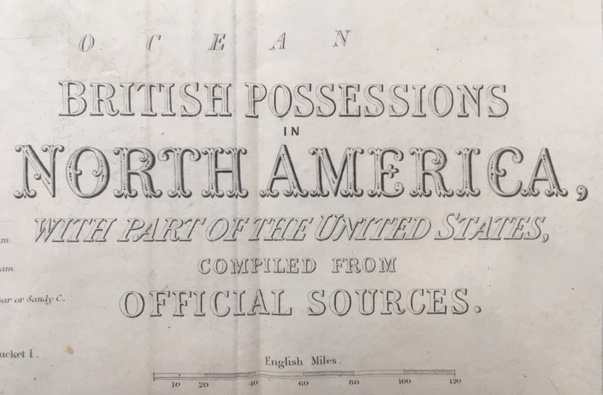

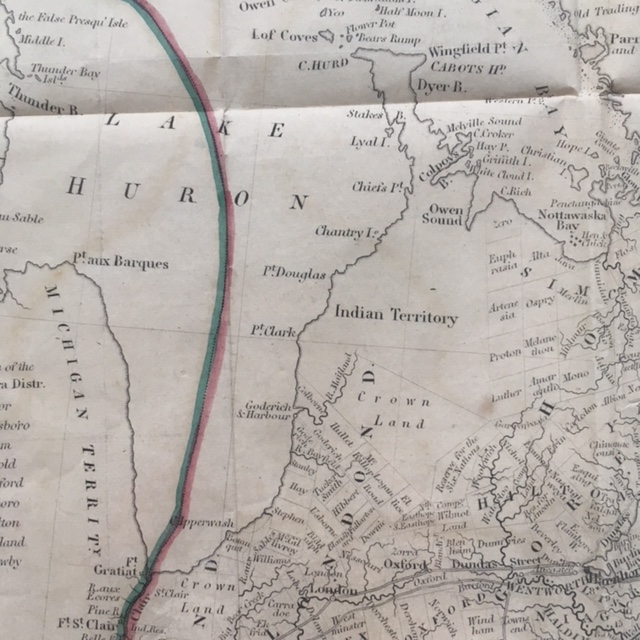

At a separate gathering last fall, I found myself in a conundrum: to participate—or not—in a North American Indigenous ceremony in Europe. I chose to not participate and begin to explore why it did not sit well with me (what I figured out can be found in this post: Colonial blind spot).

At this gathering we were not in the shape of a traditional conference, rather in the shape of listening, a circle, so I spoke what I was struggling with: that the use of an Indigenous ceremony by Europeans without the acknowledgement of the European colonial involvement in the attempted cultural genocide of North American Indigenous peoples did not sit well with me. A few others spoke of other forms of discomfort with the ceremony and somehow, despite being people good at listening and hearing and discerning, we did not know how to handle the uneasiness in our midst. The discomfort did not have a place to land and we who felt and spoke it were left sitting with our unease without the felt awareness or support of the wider community. We were left outside.

The discomfort did not have a place to land and we who felt it and spoke it were left sitting with our unease without the felt awareness or support of the wider community. We were left outside.

Two yellow backpacks

As I made my way through these two experiences, two women sporting yellow backpacks arrived to help me make meaning of them. Both are extreme explorers of the world, comfortable in their own skin and being their own self even it they don’t quite fit the ‘norm’. They both arrived when I needed them.

Yellow backpack #1 is Willemijn, who whisked me off to The Hague after the gathering in Europe. With a handful of compatriots, the Netherlands was revealed to me in the most beautiful fashion: by bicycle, by train, by bus and tram, by car; with guided tours of their favourite things; by sharing family and favourite food; and with time for me to explore on my own. Willemijn opened her home and her life to me, adjusted her schedule to fit me in. We got to know each other and appreciate each other. We had time to simply be with each other and talk about many things we found we shared in common. She coordinated the communication with her compatriots to help us find time together too. What she mostly did was share herself and it was beautiful and generous.

Yellow backpack #2 is Celine, who co-hosted a session with me at the traditional conference. We resisted the conference inertia and took our space in the conference to make room for participants to explore their own expertise. Afterwards, we decided to share a meal and found ourselves in an intense conversation about deep personal matters. After having revealed a bit of ourselves to each other with our conference session, we found in each other an instant trust and safety from having revealed. We both tuned in to there being more for us to explore with each other and we both said yes. It started with an unusual conference session where we were allowed to speak to each other. We were able to notice an interpersonal connection and then act on it. (Noticing interpersonal connections is not encouraged at traditional conferences by design, despite intention otherwise.) What she mostly did was share herself and it was beautiful and generous.

I met Willemijn first and had been feeling like she was a guardian angel sent to tend my hurting soul. We didn’t even talk about what was hurting; we enjoyed each other’s company and it was perfect. When I met Celine two months later, I first noticed her yellow backpack, just like Willemijn’s, and how they contain the essentials needed for the day, to serve its porter well. (It always amazes me what comes out of a backpack!) I also noticed how the cheery yellow backpack reflects the spirit of these two souls who make their way through the world with a happy confidence in doing things a bit differently than the norm. The backpacks are a bit dirty because they are well used; these are gals with practical life experience, around 30 years old, charting their unconventional paths with confidence.

What made me look more closely at the yellow backpacks and these two gals was the depth of conversation in which we easily found ourselves.

What made me look more closely at the yellow backpacks and these two gals was the depth of conversations in which we easily found ourselves. Their openness to drop in and be honest and real about themselves and with another, was spectacular. As I listened to Celine, I could not stop thinking of Willemijn and her yellow backpack. I knew I had more to notice here when I heard Celine say that she is learning to play the cello – just like Willemijn. There just can’t be that many awesome yellow backback-sporting cello-learning 30-something-year-olds in the world, can there?

At 48 and recently single, these two yellow backpacks are a reminder of what I already knew:

- I love that my life path is a bit unconventional

- My body feels great when I wear a backpack

- There are messages in the symbols of the wilderness of the human experience

- There is more going on in a conversation than what we say, or the shape/form the conversation takes

- Good conversation matters

Find and meet

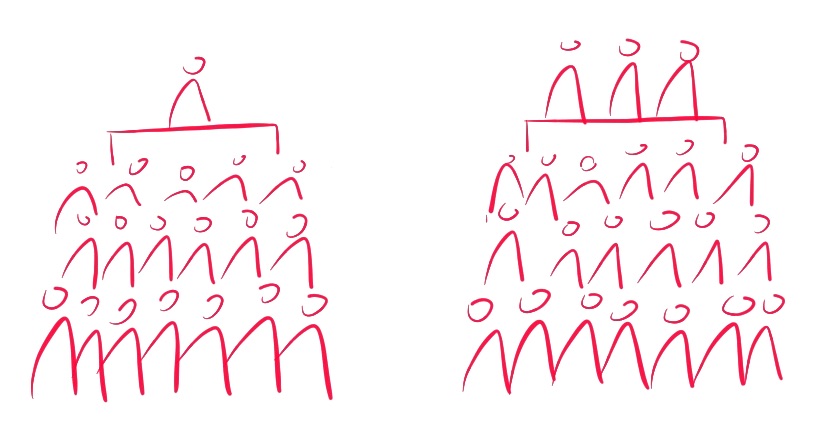

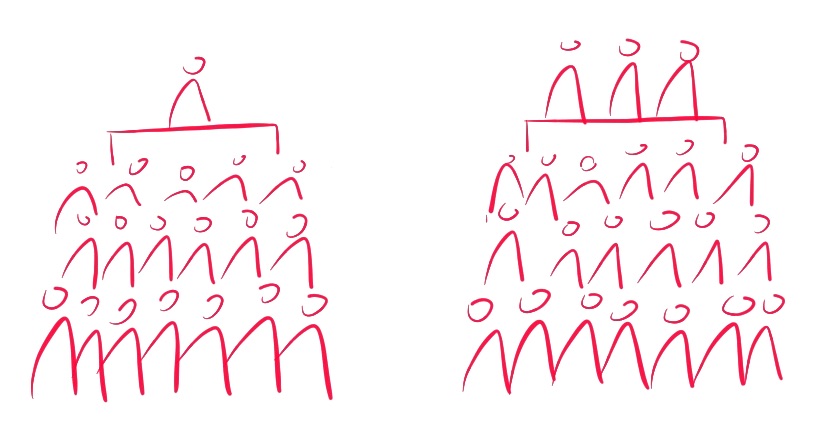

Conference design has an energy that keeps the experts and participants separate from each other and, most importantly, keeps the participants separate from each other. Unconsciously and consciously, this is by design:

Whether there is one expert at the front of the room, or a panel, the effect is the same: expert and participants. Furthermore, in this format the participants are not expected or allowed to talk to each other. In an environment like this participants (and speakers too) might see each other across the room, session after session, but rarely speak to each other, and if they do it is more rarely substantial. We speak with those we know, lightly with those we do not know, and often not at all to those we do not know.

A loaded program of presenters and people sitting to listen to those presenters allows minimal community – the people in the room share a similar interest and do not talk to each other. The energetic emphasis on the design is on expert content, not creating the conditions for people to magically find each other. At this particular conference there was great emphasis on conversation in between conference sessions, and there is a significant limitation to where those conversations will go because they have little to build on from the conference itself – interpersonal connections are not cultivated. We keep our distance because we only, perhaps, see each other when we choose similar sessions, but we don’t ‘find’ each other. We don’t ‘meet’ each other. Even over coffee, we keep our distance.

We keep our distance because we only, perhaps, see each other when we choose different sessions, but we don’t ‘find’ each other. We don’t ‘meet’ each other.

What I mean by ‘find’ and ‘meet’ is this: we share ourselves beyond a simple shared interest; we share stories and struggles and tap in to our collective wisdom; we give our ourselves and receive in return. It may be two of us or twelve or two hundred. But to do this, we have to let go of the sage on the stage—the expert outside of us—and trust the expertise within and among us as a community. When we don’t trust our own expertise we block our ability to access our own expertise.

Enable natural hierarchy

When people find themselves in the same place at the same time a community of shared interest becomes visible, and because of this we can feel a sense of community, particularly when we are felling isolated. The mere existence of ‘people like me’ brings elation. There is more to community than this when we choose to consciously weave ourselves together, which amplifies our sense of community. And if that community sits in a circle, that shape itself is not enough if the field of relationships between us is not sufficiently nurtured.

If a community sits in a circle, that shape itself is not enough if the field of relationship between us is not sufficiently nurtured.

Circle is form of meeting where leadership is shared and a diversity of perspectives is welcomed and accommodated. This is also an environment in which ideas in conflict can be difficult to handle if power imbalances are not acknowledged.

If a circle is flat, with no hierarchy or resistance to hierarchy, there is no room to acknowledge power imbalances—and diversity of life experience. A flat circle resists conflict because it wants to consider itself peaceful and welcoming no matter what, even if the opposite is the case. A flat circle, despite its claim to welcome diversity, remains shallow in experience, meaningful only for those on the inside. There isn’t room for those with an ‘outsider’ point of view.

A not-so-flat circle acknowledges the subtle and explicit hierarchies that naturally occur in human systems and explores them.

A not-so-flat circle acknowledges the subtle and explicit hierarchies that naturally occur in human systems and explores them. In doing so, conflict can be held, explored and resolved. This is a circle that endeavours to hear itself and the power dynamics within, and this accommodates more diversity.

Acknowledging the natural occurrence of hierarchy is enabling, both from the structural support it provides, but also as a topic of conversation that allows us to see ourselves better. When we allow ourselves to talk about power, real and perceived, we see our relationships far more clearly. When we don’t, we block ourselves from creating community beyond the sharing of a common interest.

Community means belonging

We feel community when we feel we belong. We can share a family bloodline, or share geography, in a neighbourhood or city. We can feel community in an organization of any size. We can feel community in social media as we find people with shared interests across the planet. This experience can be meaningful and superficial at the same time (this is often just the right thing!), or it can be meaningful and involve being deeply held as we make our way through the challenges of life as individuals and as communities. As we find ourselves increasingly challenged with the pace of change and conflict in our world, being deeply held and having the capacity to hold and examine conflict is essential. We need to do a better job of finding and meeting each other.

As we find ourselves increasingly challenged with the pace of change and conflict in our world, being deeply held and having the capacity to hold and examine conflict is essential. We need to do a better job of finding and meeting each other.

The conference participants shared an interest in building community sustainability and the standard conference design fostered surface belonging. Community resilience is fostered when a range of ways of being in relationship are activated in the community, ways that reach below the surface of a shared interest.

The circle gathering participants shared a way of meeting (in circle) that fosters conversation in ways that reach below the surface. In this case, when community struggles with noticing and acknowledging power imbalances, it resists the diversity needed to enable resilience.

A resistance to welcoming and accommodating non-expert or outsider perspectives was present in both gatherings in explicit and subtle ways. It manifested as a resistance to talk to each other and invite the outsider in. In both cases, there was a yellow backpack in the room, sitting there, waiting to be unpacked, waiting for its mysterious contents to be revealed and examined. And for the people who gather round to invent their way forward in the mutuality of community.

In your experience, what enables community to welcome and explore the outsider?

ps – so far, I am resisting the urge to acquire a yellow backpack as I already have too many backpacks…

Recent and related posts

- The unspoken – a poem on the question of what to do when you find yourself holding the unspoken.

- Colonial blind spot – People of European lineage – if we are not accepting our story of attempted cultural genocide, we are causing harm. We are propagating the bliss of ignorance.

- Care out in the open – Care needs to be out in the open or it isn’t happening. To care out in the open means I am willing to be changed by what I hear.

- Harm happens, intended or not – A welcoming city examines how it defends itself from change, how it maintains the status quo by denying that others are harmed.

- A welcoming city has transportation choices – All people, regardless of their chosen mode of transportation, exhibit care and look out for each other. That’s how it works: accommodation.