A community in conversation with itself does not rely on others to have the conversation on its behalf–the community is involved in the conversation.

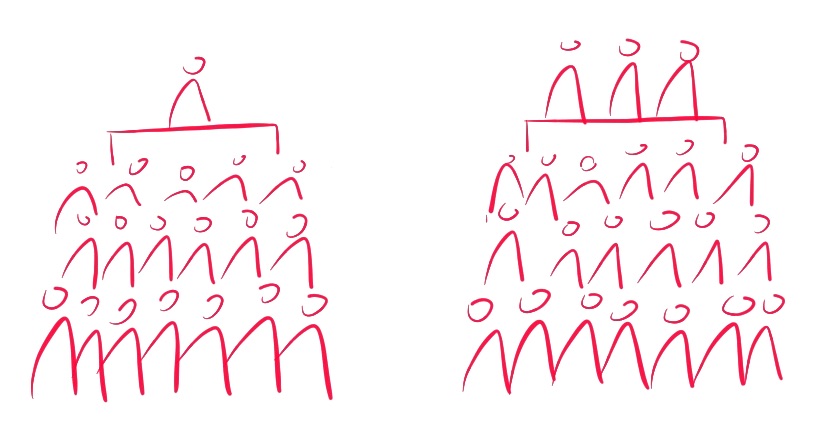

A city (or group or organization) that brings in experts for a speakers’ series is not in conversation with itself. A city that brings people together to hear from someone (but not from each other) is not in conversation with itself. A city that presents a panel discussion that hundreds of people listen to is not in conversation with itself; it is a city that watches a handful of people in conversation about the city. The conversation is separate from the community, even when right in front of the community that has gathered.

The nuance here is significant, and you can catch it with a simple two-part question: who is involved in the conversation, and is there an opportunity for them to figure things out for themselves?

Who is involved in the conversation, and is there an opportunity for them to figure things out for themselves?

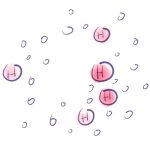

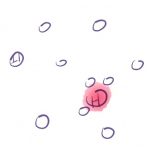

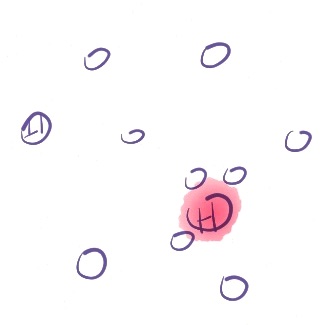

Even when we are in the shape of community–a circle–it is possible for a community to not be in conversation with itself. This occurs when we lose track of the energetic pattern of the gathering. (For more information, please see these two previous posts: host-attractor and host-on-the-rim, and roles and challenges for the host-attractor and host-on-the-rim.)

In two posts last year, I explored two patterns–the host-attractor and the host-on-the-rim–and the challenges we experience with them. In the case of the host-attractor pattern, the primary challenge is the expectation that the hosts will have all the answers and that participants will not question hosts. The danger in this is that the community will go where the host wants them to go, from a host-ego place that is not in service to the community’s learning process. In the host-on-the-rim pattern, the primary challenge is reluctance in the community to share and rotate the hosting work. The danger in this case is that the group will go where a few people want to go, rather than discerning where the whole group is wanting to go. The result is a wobbly circle.

Two examples of wobbly circles

The challenges in each pattern are about power dynamics and the power we give–consciously and unconsciously–to hosts or community, to a handful (or one) or to the whole. While each pattern in isolation appears to have distinct challenges, it is not a binary, either/or matter. Most often, the patterns are activated simultaneously, which creates significant challenges to the well-being of our social habitat because we don’t know which direction we are aiming to move toward: the expertise in others or the expertise in us. The latter disempowers community and separates us from ourselves, while the former empowers and moves us toward wholeness.

The challenges in each pattern are about power dynamics and the power we give–consciously and unconsciously–to a host or community, to a handful (or one) or to the whole.

These challenges appear under any of the following conditions:

- When a community is strongly attracted (consciously or unconsciously) to one or a few of its members and minimizes the contributions of others

- When a community strongly resists (consciously or unconsciously) the contributions of one or a few of its members

- When a community member has a strong desire (consciously or unconsciously) to be a host-attractor in the group

- When a host-attractor does not want (consciously or unconsciously) the attention and responsibility of being an attractor

- When a host-attractor denies (consciously or unconsciously) their presence as a host-attractor

- When a host-attractor wants to create the conditions for the community to host itself (and shift the attraction/identification from the host-attractor to the larger community)

All six of of the above scenarios involve subtle and significant power dynamics, full of shadow and projection. To best handle them, we need to be willing and able to talk about our attachments to how we perceive each other, and ourselves, in our relationships and we need to be in community to do this. Sometimes the host-attractor pattern is the right one. Sometimes we feel the need to shift into the host-on-the-rim pattern, what one reader (thanks Ian!) framed for himself as “host-as-all-of-us”. But if we are in the host-attractor pattern, relying on the guidance of others rather than our own guidance, we are not in a community pattern.

We need to be willing and able to talk about our attachments to how we perceive each other, and ourselves, in our relationships and we need to be in community to do this.

Ten years ago, six of us gathered around a teacher to learn specific material in a clear host-attractor pattern. We gathered around because we were attracted to both the teacher and the material she would teach us that would nourish our individual learning journeys. She laid out clear expectations about what we would learn, how we would learn it, and what she expected of us as participants. She created the conditions for us to get to know each other as a learning community ourselves and we choose to step into this during our time with her as a host-attractor.

Most learning events create a community of shared interest, where we find people ‘just like me’ for a time, and we are buoyed with a sense of belonging. When the event is over, the connection dissipates because the sense of community stemmed from identification with the host-attractor, not the community around the attractor. In its power to create community, the host-attractor energy is not long-lasting.

Most, but not all of us, chose to stay in relationship with our teacher after the training was complete and gathered regularly, as teacher and students with shared interests. After a while, the gap between teacher and students lessened and we made a transition from a host-attractor circle to a host-on-the-rim circle. Our teacher’s role changed dramatically, as did ours. We all had to remind ourselves that we were no longer looking to our teacher to organize us, host us, and teach us–we were doing that for ourselves. We all had to allow a melting away of our earlier relationship into a new one, and we spoke about it as we did it.

While the above example is a small community of 7, this phenomenon is scalar; it applies to groups of any size, including organizations and cities.

I wonder what it would mean for a city to embark on a host-as-all-of-us journey, for citizens to be in conversation with ourselves about who we want to be as a city, and what it will take to be that city? Yes, people with expertise need to be involved, but the difference is the acknowledgement that there are various kinds of expertise that need to be integrated into city intelligence and this means those expertise need to be in conversation with each other. The perspectives of the city need to be in touch with each other.

I wonder what it would mean for a city to embark on a host-as-all-of-us journey, for citizens to be in conversation with ourselves about who we want to be as a city, and what it will take to be that city?

The shapes of our conversations, and how we host them, create social habitats that allow for–and disallow–this kind of integration. It is easy to listen to sage on the stage, for that is a comfortable pattern because it is familiar and there is less work for us to do as citizens. A city in conversation with itself does the tough work to integrate a wide range of perspectives and experiences.

A city in conversation with itself does the tough work to integrate a wide range of perspectives and experiences.

REFLECTION

Take a moment, on a walk or with a journal, or whatever works for you and ponder these questions:

What is the default in your city? Do you show up to community events and find yourself hearing about what one or a few have to say, or do you find yourself in conversation with a variety of people with time and space to figure out what you think, and what you have to say?

This is the fourth post in a series about “how much of me” to put in while hosting community that wants to be in conversation with itself. The first version of this appeared in Nest City News, February 15, 2019.

- Host-attractor / host-on-the-rim

- Roles and challenges for the host-attractor and host-on-the-rim

- 8 strategies to navigate power patterns

- A city in conversation with itself; shifting to host-as-all-of-us