I watched two men well into their 60s get into a physical fight at the ski hill yesterday. I’d taken a break to sit in the sunshine and give my knee a moment to tell me if skiing was a good or bad thing to be doing. I watched a family of three ski up beside the chalet. The woman in her late 40s stepped out of her skis and headed into the chalet. The man (man #1) in his early 60s and a boy of fifteen then stepped out of theirs and walked into the chalet. As I watched this unfold, I had a feeling I should go and tell them that they should put their skis in the racks, rather than leave them laying about, but I chose not to say anything. I also chose to not go and move them myself. My rationale: “it’s a quiet Monday April 30 at Marmot Basin, there’s hardly anyone here, I don’t have much energy for this and what does it matter?” It mattered when a handful of people had to dodge their skis when they came upon them unexpectedly, one of them another man in his 60s.

Man #2 marched up to the skis and picked up a pair and some poles and threw them toward the racks, then another a violent swing of skis. His hands were on the last pair when I saw man #1 heading toward him with great speed. He pushed straight into man #2 with a shove, shouting, “don’t throw my skis”, and they pushed and shoved, with man #1 trying to throw punches. (It still seems stupid to me to fight with a man with a ski in his hands.) In seconds a man nearby was shouting at them to stop, soon joined by the woman now out of the chalet. After a few moments, when man #1 let go, man #2 walked away. I could hear snippets of the woman telling man #1 that his behaviour was bad, that it is important to notice the etiquette of a place and do what is expected, and how he was treating her was not ok.

Violence is not only physical, it is emotional, so do what you need to do to look after yourself, because you’re worth it.

Now ready ski myself, I had to move by this family of origin to get my skis and ski over to my kids now waiting for me. I paused to say I saw what happened and man #1 snapped at me, so I moved on. The woman stopped me, wanting to know what I saw. I told her: man #2 threw the skis and he should not have done that. I came to say I saw you leave them in a bad place and I chose not to tell you to move them, and I should have. And your man’s reaction to the situation was both inappropriate and way out of proportion.

In a moment, I learned from her that he does not hit her, or is physically rough with her, that they have no money in their shared bank account but he has an unknown amount separately, enough to fund an impromptu trip to Mexico with a hunting buddy.

I said to her, reminding her that I am a total outsider who knows nothing about her situation other than what I just saw, this: violence is not only physical, it is emotional, so do what you need to do to look after yourself, because you’re worth it.

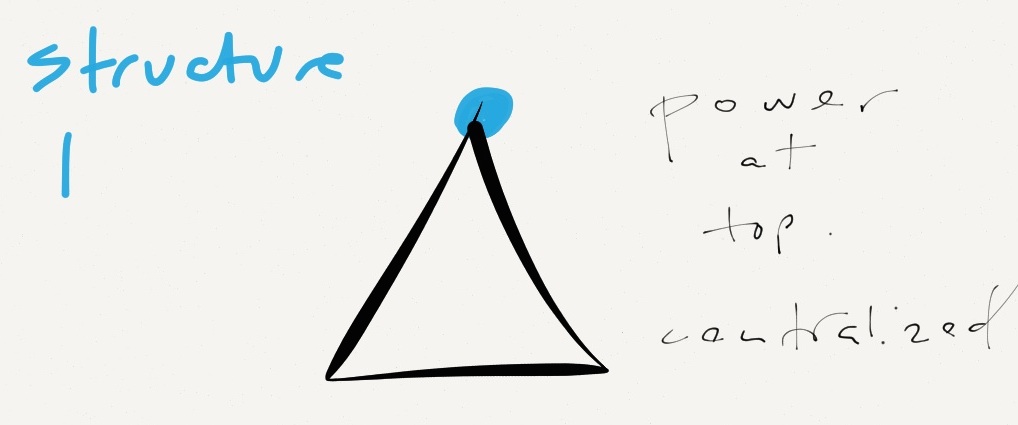

What I did not say to her: when you exercise your sovereignty (I like the language of sovereignty that Heather Plett uses), he is not going to like it. When you put in place the boundaries you need to be not only safe, but healthy, he is not going to like the changes to his life that come with that. He will find the new you disturbing and destructive to his sense of self and he will do everything he can to claw you back into that place that is unhealthy for you–even while telling you he loves you and supports you. In simple terms, he will do this because he won’t like that it means his world must change. In simpler terms, he won’t want to lose the benefits he enjoys with his power over you in the current arrangement.

What I did not say to her: when you exercise your sovereignty, he is not going to like it… He will find the new you disturbing and destructive to his sense of self and he will do everything he can to claw you back into that place that is unhealthy for you–even while telling you he loves you and supports you. In simple terms, he will do this because he won’t like that it means his world must change. In simpler terms, he won’t want to lose the benefits he enjoys with his power over you in the current arrangement.

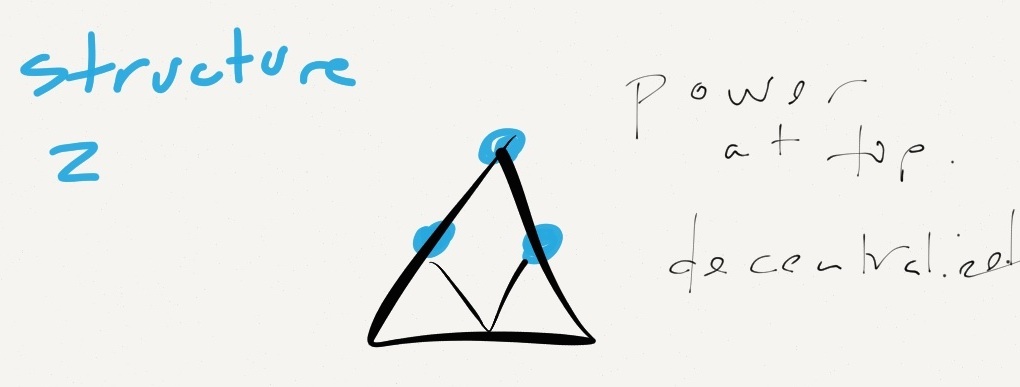

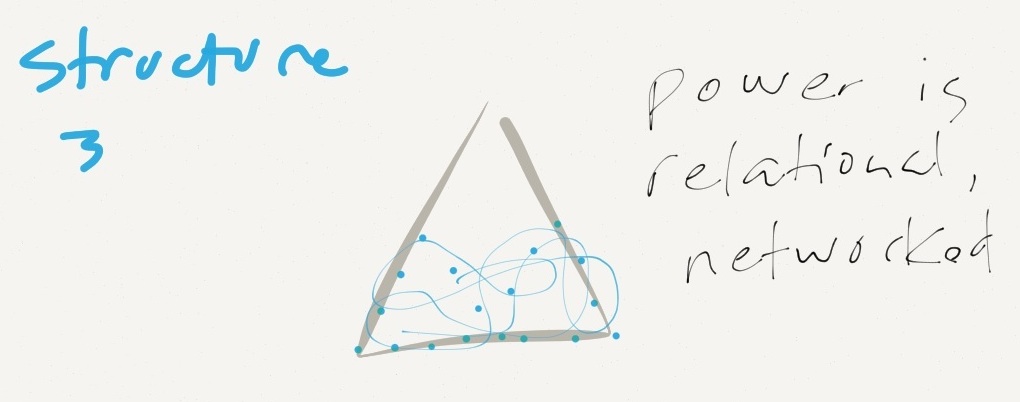

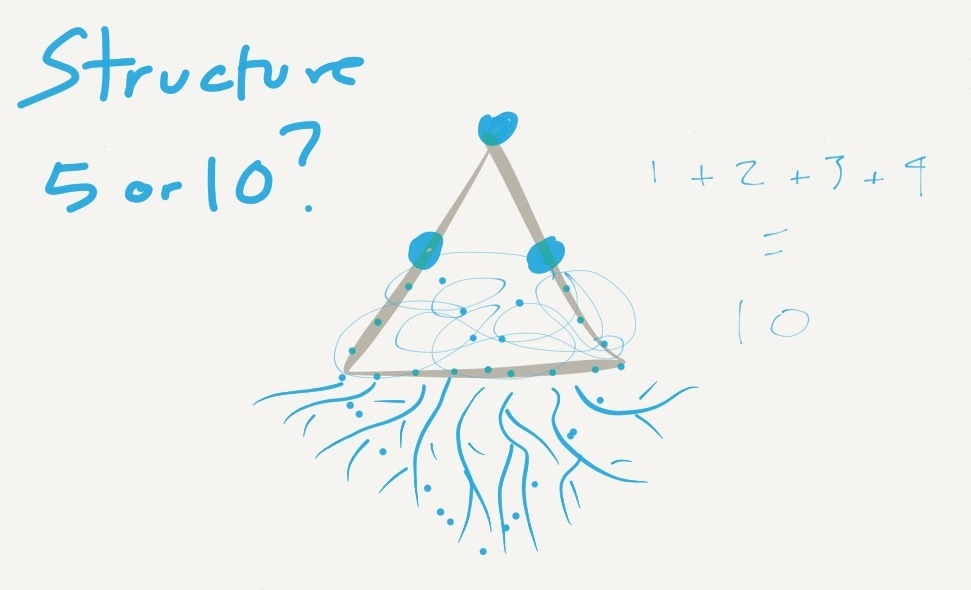

To be in relationship without the power imbalance will require two things: she has to do the emotional labour of figuring out what she needs, speaking it, and demanding what she needs when necessary, and he has to do the emotional labour of receiving it and allowing his sense of identity to shift, even be radically changed. She may choose to stay under his power, and he may choose to work hard to keep her there. They will both choose what they are capable of handling (without judgment).

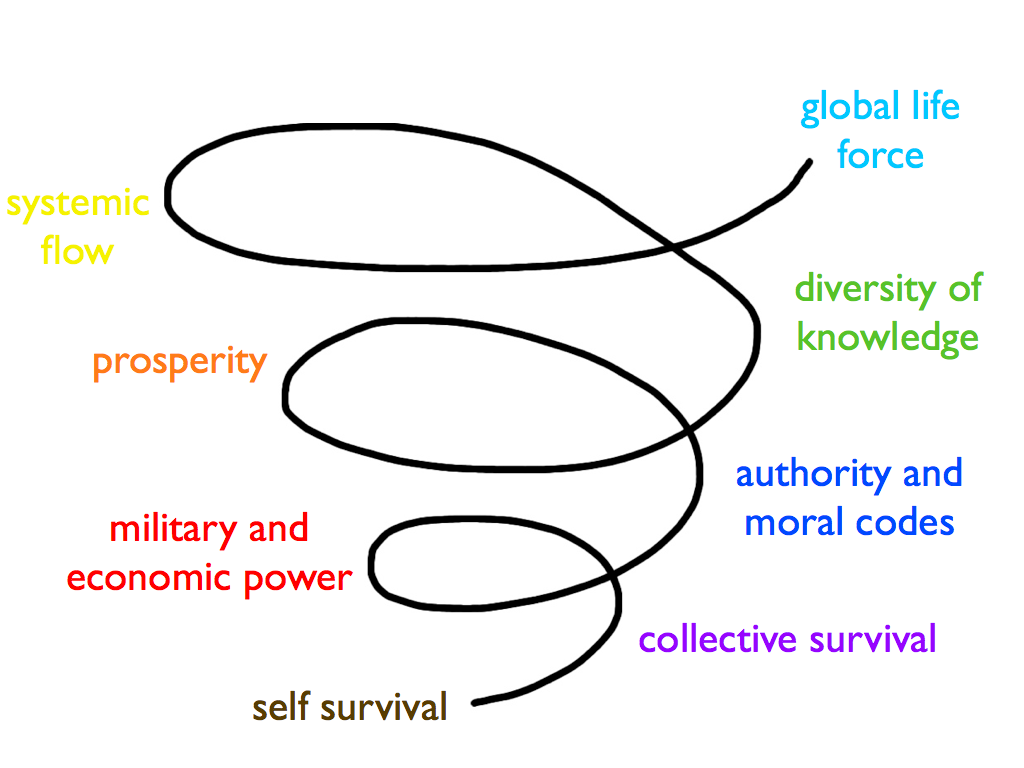

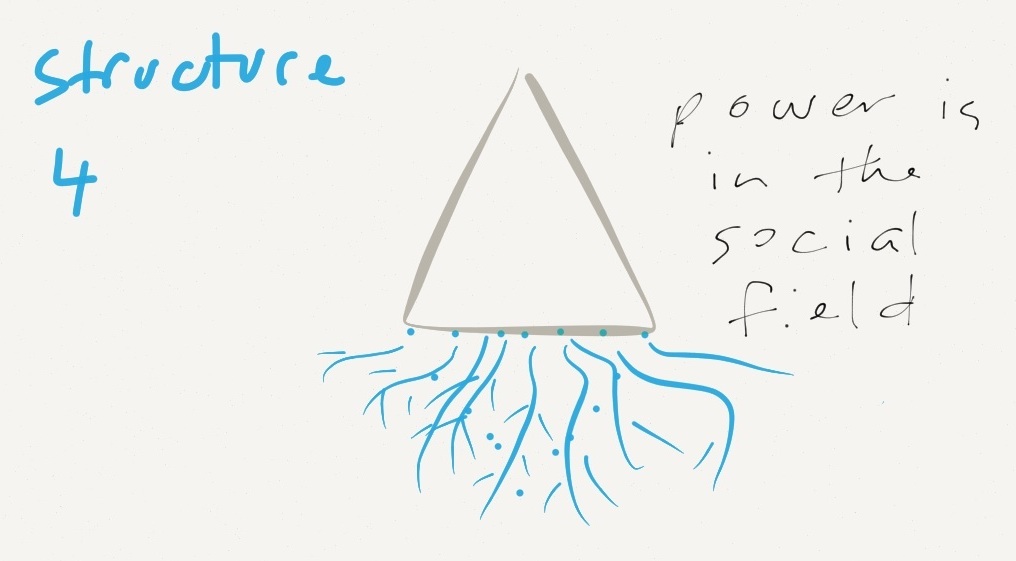

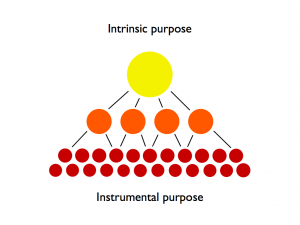

This microcosm of power dynamics is playing out at much larger scales right now. People are figuring out what they need and speaking it and demanding it (#metoo, Black Lives Matter, or the Truth and Reconciliation Commission work in Canada) and those of us in power have a choice: deny and fight, to protect against threats to our sense of identity and power, or accept and welcome the changes that come with finding new ways to live together that are equitable, not skewed in favour of us.

Those of us in power have a choice: deny and fight, to protect against threats to our sense of identity and power, or accept and welcome the changes that come with finding new ways to live together that are equitable, not skewed favour of us.

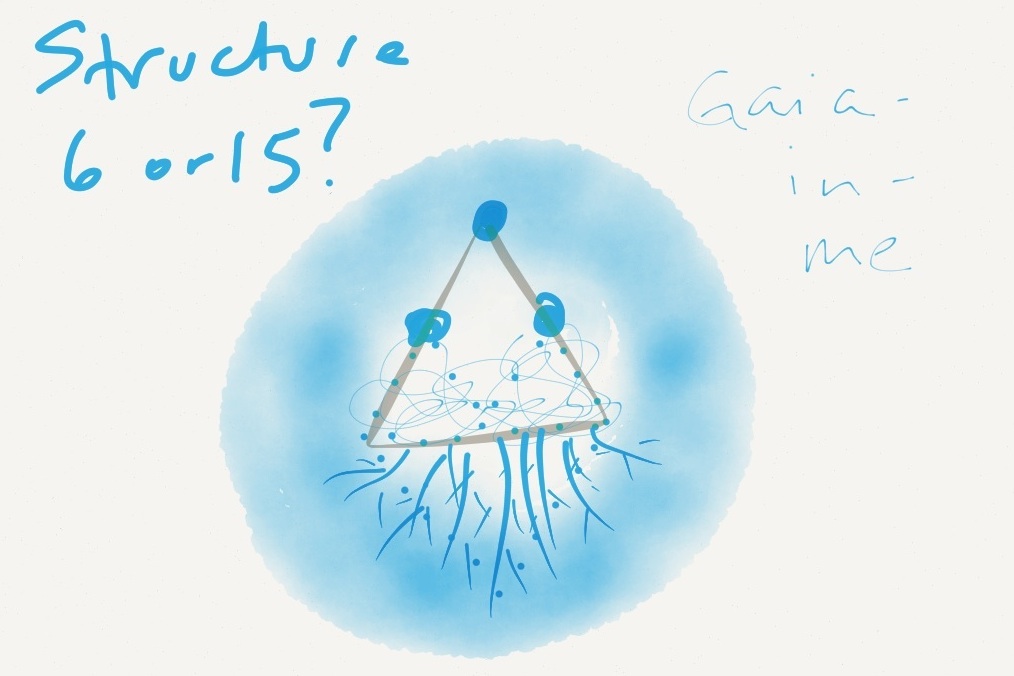

I include myself in the ‘us’ here as I have enjoyed and continue to enjoy a life of white privilege. Here’s a question I ask myself: “How does what others share about their experience threaten my sense of identity, and how does that sense of threat lead me to deny their experience so I can maintain my position of privilege”? Deep down, I have a choice about whether to fight to maintain the status quo and my place of privilege, or do the inner work that allows my sense of self to grow into understanding the conscious and unconscious ways I benefit from being white. It is from here that I am able to support others in their growth into their sovereignty without continuing to threaten or harm them.

At small and large scales, this is about how the experience of those who have experienced less power historically is allowed and invited to change the identity of those enjoying power. This is not easy work, for anyone, and it is necessary. It is a struggle about power.

There is the difficult work for the people who exercise their sovereignty—tell of their experience and what they need—and experience and withstand the backlash. There is the difficult work for people traditionally holding power now told to find a way to accommodate the rising sovereignty.

And then I think of the two white men in their 60s, enjoying a day of skiing with friends and family (a privileged life just like mine), fighting each other to protect their skis (not like me). For a moment, a part of me thought we should be supportive of men like this, men I imagine are having a hard time with the pressure to change who they’ve always thought they’ve been (i.e., it’s not ok to touch women when without consent, it’s not ok to deny the experience of People of Color, it’s not ok to deny the attempted cultural genocide of Canada’s Indigenous peoples). It was only a moment before I realized these men are stand-ins for all people who experience the benefits of power, and this pressure to no longer be who we’ve always been is not to be denied; this pressure is necessary and it needs to be experienced or we, as a whole species, will not move through it.

These men are stand-ins for all people who experience the benefits of power, and this pressure to no longer be who we’ve always been is not to be denied; this pressure is necessary and it needs to be experienced or we, as a whole species, will not move through it.

We are all moving through a recalibration of power relating to any form of inequity (gender, race, etc.). Most often, change only happens when we are sufficiently uncomfortable. Writ large, denying ourselves discomfort is not helpful to our growth as individuals and as a species because we need that discomfort to improve ourselves. White culture, men and boys, or whoever is on the better side of a power imbalance, do not get to dodge the truth of harm because they feel ‘harmed’ by hearing about the harm they’ve caused, or ‘harmed’ by the consequences of their actions. Harm and hurt are not the same thing; when my bad behaviour is pointed out, I am not harmed, I am hurting (though I may feel harm if I have escalated my reaction to be highly defensive of my sense of self).

Telling each other what we need to tell is uncomfortable and necessary. Hearing what we don’t want to hear is uncomfortable and necessary. It hurts. We may feel—or be told—we are causing harm by doing this, but we are causing more harm by not speaking and receiving what needs to be said.

Telling each other what we need to tell them is uncomfortable and necessary. Hearing what we don’t want to hear is uncomfortable and necessary. It hurts. We may feel—or be told—we are causing harm by doing this, but we are causing more harm by not speaking and receiving what needs to be said. Exercising sovereignty is disruptive, as it should be, because it compels us to honestly look at how we relate to each other.