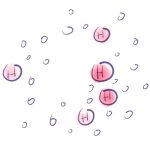

Under the summer sun, fifteen kids, ranging in age from 6 to 10 years old, and two adults filed on to the bus last week, collecting behind me, near the back of the bus to keep the group together. I imagined the fun of a summer field trip until the adult camp leaders started talking. They were caught up in fight drama, full of fight energy. It was subtle, and infectious as it spread around the bus. If there was any fun on that field trip, it was not fun any longer.

It was subtle and infectious as it spread around the bus. If there was any fun on that field trip, it was not fun any longer.

The camp leaders were mad because they were running late. The group of them had been standing at the side of the road in between bus stops expecting the previous bus to stop for them. It did not, and they were furious. “What else would he be thinking? Why else would a group of kids be standing there? I called to make a complaint and they wouldn’t take the complaint because we were not at a stop–how ridiculous is that?”

A nearby woman chimed in: “Those bus drivers! Not all of them, mind you, but there are enough around that just don’t care about people.” They went back and forth for a few minutes. In front of me, two women who did not know each other started to talk about it by themselves: “What a shame. Bus drivers these days. You can call 311 and make a complaint, but would they even listen? Would they ever change?” (Note: they didn’t hear the words of the camp leaders. They did call 311. It was the fight-feeling that was spreading.)

I found myself wanting to get off of the bus.

I wanted to escape the spreading infection of negativity and criticism and blame. I did not have the energy to witness the tempting pull to dehumanize, and demonize people we don’t even know. My stop arrived a couple minutes later and I stepped off, relieved.

As I walked home, I thought about it and noticed that the camp leaders were:

- Experiencing anger about the bus not stopping for them.

- Experiencing frustration that they were running late.

- Voicing their anger and frustration out loud.

- Blaming the bus driver for their anger and frustration.

- Looking for and securing allies to justify their view.

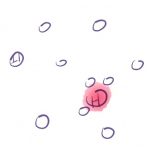

In that moment, they had hearts at war, as The Arbinger Institute, in The Anatomy of Peace: Resolving the Heart of Conflict, calls it. They needed to find others to blame, rather than try to understand the situation of the other (the bus driver who drove by) or take personal responsibility for their situation.

In that moment, they had hearts at war.

When the heart is at war, we see and experience the world in a specific way. Here’s a summary of how The Arbginger Institute describes the heart at war:

- View of the world: unfair, unjust, burdensome, against me

- Feelings: angry, bitter, justified, impatient

- View of myself: better than, a victim (I am owed), need to be seen well

- View of others: wrong, incapable, inferior (or superior)

I know this stance. It is a regular occurrence in my life that I have to pay attention to with my family, friends, clients and the people I work with. From this stance, I am not able to see others as people; I see them, and experience them and treat them, as objects. When I operate this way, everything is going wrong and everyone else is to blame. When my heart is at war, I view the world as unfair and unjust, which leads me to feel anger, bitterness, and justification. When I feel this way, I may view myself as better than others, or as a victim that is owed, which means that my view of others is that they are wrong, incapable and inferior, or even superior to me. And I will look for and encourage allies to support me in this stance. It often feels like an easy way to operate, and it can take a great deal of energy to knock myself out of it.

In contrast, a heart at peace, also described by The Arbinger Institute, is a very different quality of being. Instead of viewing others as dehumanized objects, I view them as people, with hopes, needs, cares and fears as I have, and not more or less important than mine. There are two ways of being:

|

HEART AT WAR

|

HEART AT PEACE

|

|

Others are OBJECTS: obstacles, vehicles, irrelevancies

|

Others are PEOPLE: hopes, needs, cares, and fears as real to me as my own

|

The stance of a heart at peace appears to be hard because it involves a degree of self-awareness, and a willingness to notice what is happening within me. For The Arbinger Institute, we each, in every situation, have a sense of what we’d like to do, or how we’d like to be. The path to a heart at war is in the betrayal of that desire. Honouring that desire allows me to maintain a heart at peace. If I do not, I begin to see the other in ways that justify my self betrayal. It takes practice, and with practice it becomes easier. Over time it becomes easier to tell fewer lies to myself.

Over time it becomes easier to tell fewer lies to myself.

Did the camp leaders betray themselves?

I am only imagining here… Did they mean to give themselves more time to get to the bus stop, but did not? Did they sabotage this plan and then in anger and frustration blame it on someone else? Are they so entrenched in a heart at war stance that they don’t even know they’ve done this, or was it an infrequent occurrence? (Perhaps they took personal responsibility later, but in the moment they did not.)

Were they aware of the example they were setting for the children in their care, to blame things always on someone else? Deep down inside, did they feel badly and chose instead to justify their indignation and recruit allies to the cause?

Deep down inside, did they feel badly and chose instead to justify their indignation and recruit allies to the cause?

(In contrast, I imagine a couple camp leaders and vibrating kids getting on a bus in conversation with each other, kids and adults intertwined. “Did you see that skeleton? Did you notice how big the horns were? Did you see that room full of bugs — which one was your favourite? Oh, I couldn’t go in that room, it was too scary, but I liked the video of the old man talking about the medicine wheel.” Full of joy and revelling in the shared experience of the trip, and, perhaps, one of the adults saying, “Oh my, I so wish that bus driver saw us waving our arms like crazy when we were caught between bus stops. We must have been funny looking!)

In a spirit of having a heart at peace, and not a heart at war, I try to imagine what it was like to be those camp leaders. I have no idea what their day was like up until that point, or the trouble they will be in if late. I have no idea what their life is like, any trauma that they are dealing with. All I can do is notice how they showed up, and how their energy–not necessarily them–recruited others.

All I can do is notice how they showed up, and how their energy–not necessarily them–recruited others.

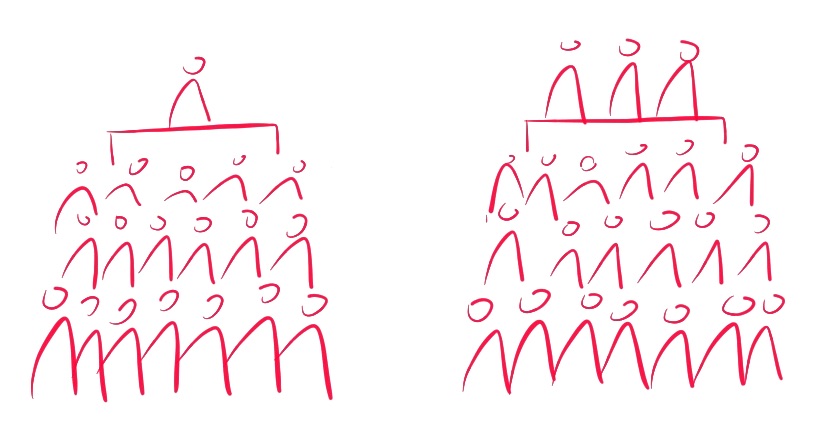

This heart at war dynamic is akin to the prevalent war mentality that Charles Eisenstein articulates in his book, Climate: A New Story. A war mentality is a stance “based on a kind of reductionism; it reduces complex interconnected causes–that include oneself–to a simple, external cause called the enemy. Furthermore, it normally depends on the reduction of the enemy to a degraded caricature of a human being.” The ‘other’ is therefore “undeserving of reverence and respect, an object to dominate, control, and subjugate.” The camp leaders were operating from a war mentality, demonizing the bus driver and Edmonton Transit Service, and when another joined in they kept going. The camp leaders and the bystander joined forces. Others drew in this anger and riled themselves up.

This war mentality is in play in so many of our human interactions. The war on terrorism. The war against climate change. The war on drugs. The war on racism. It even drifts into the war on bus drivers. This mentality is pervasive and the irony is that it maintains the status quo:

…fighting the enemy is futile when you inhabit a system that has the endless generation of enemies built into it. That is a recipe for war.

If that is to change, then one of the addictions—more fundamental than the addiction to fossil fuels—that we are going to give up is the addiction to fighting. Then we can examine the ground conditions that produce an endless supply of enemies to fight (Eisenstein, p. 17).

When the fighting never ends, the power structures remain the same; all we do is shift who has power and who does not. (Think about the Game of Thrones: endless fighting and all that changes is who sits on the iron throne. And you can never be sure you’ll be there for long.) The “ground conditions that produce an endless supply of enemies to fight” are the heart at war. In the end, then, the question is, who do we want to be? How do we want to be?

The “ground conditions that produce an endless supply of enemies to fight” are the heart at war. In the end, then, the question is, who do we want to be? How do we want to be?

Do we want to maintain a clear separation between us and them, between right and wrong and maintain the game as we know it? Or do we want to make the transition to a world where conflict is not about right and wrong, but a way to make sure others’ needs are met, because in so doing mine will also be met?

IMPORTANT NOTE: Conflict does not disappear when we stop operating in fight mode. I do not advocate that conflict be ignored. We desperately need to talk about what works and does not work for us and work to resolve it. Instead of reverting to a war mentality of fighting and dehumanizing, we grow our capacity to be in conflict in ways that allow people’s needs to be met. This involves a lot of work within self, with others, and in relationship to the places we call home.

VERY IMPORTANT NOTE: I am not advocating no fighting under any circumstances. Like Eisenstein, I observe that being in fight mode all the time is not effective. There are instances where fighting does make sense: human rights violations, racism and genocide, ecocide.

The infection that spreads, then, is not fight drama, but deep and meaningful, interconnected relationships: the ground conditions for support and care for self, others and the places we call home.

The choice at hand for each of us: Which infection do I choose to spread? The anger and frustration that comes with fight drama, or the generative possibility that comes with exploring conflict?

Resources:

Charles Eisenstein, Climate: A New Story, North Atlantic Books, Berkeley, 2018.

The Arbinger Institute, The Anatomy of Peace: Resolving the Heart of Conflict, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., Oakland, 2006, 2008, 2015.

The choice at hand for each of us: Which infection do I choose to spread? The anger and frustration that comes with fight drama, or the generative possibility that comes with exploring conflict?

This post first published in Nest City News on August 9, 2019.