2018 begins with a contemplation of the settler / colonizer story in me and my European cultural lineage on the Canadian Prairies. My understanding of this story and its implications has been growing over many years, most recently with a trip to Germany last fall. It was one of those trips where I realized I had to leave North America to see the story of European settlement in North America more clearly—the story of the changing nature of our nations, cities and communities and how power shows up.

I am of European descent (Norwegian, English and Irish), born in North America. My sense of home is in North America but by lineage I am indigenous to Europe, so time at a retreat center in Germany last fall came with this question:

What in Europe is indigenous to me?

Germany and Europe is the lineage of many who populated the Canadian Prairies and who I grew up with. Just over 100 years ago, my Norwegian forebears settled in New Norway, Alberta. My former husband’s forebears settled in Stockholm Saskatchewan. Settlers from Germany began arriving in Alberta in the early 1880s and came from a variety of ethnic and religious backgrounds and countries: Austria-Hungary, Switzerland, Russia, Russian Poland and Romania. By 1911, they were the largest group of non-British settlers in Alberta (Source: Collections Canada. More on German-speaking communities can be found at the University of Alberta, here.)

Many place names on the Canadian Prairies reflect settler’s homelands, such as New Norway and Stockholm. German place names in Alberta include:

- Bismarck

- Bruderheim

- Carlstadt

- Dusseldorf

- Fribourg

- Friedenstal

- Gleichen

- Gnadenthal

- Greisbach

- Hussar

- Josephburg

- Rosenheim

- Rosenthal

- Stettin

- Swastika

- Volmer

- Wagner

- Waldheim

- Wiesenthal

This is a simple and phenomenal fact: my culture arrived from Europe—we settled here—to colonize North America. Another simple and phenomenal fact: there were people already here, a sophisticated and rich culture, indigenous to this land. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada recognizes this as part of a global occurrence:

The Age of Empire saw powerful European states gain control of other peoples’ lands throughout the world. It was an era of mass migration. Millions of Europeans came as colonial settlers to nearly every part of the world. Millions of Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean in the European-led slave trade, in which coastal Africans collaborated. Traders from India and China spread through out the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, bringing with them servants whose lives were little different from those slaves. The activities of explorers, farmers, prospectors, trading companies, or missionaries often set the stage for expansionary wars, the negotiation and the breaking of treaties, attempts at cultural assimilation, and the exploitation and marginalization of the original inhabitants of the colonized lands.

Source: Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1 (p. 9-10). Includes references to Howe, Stephen. Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002 (p. 21, 22, 57).

The arrival of my European culture here was colonial. Two examples:

- The founding of Hussar, a village east of Calgary, was settled by a group of German noblemen and reservists in 1913. They created the German-Canadian Farming Company Ltd. and bought lands from the Canadian Pacific Railway to establish colonization farms in the area (for more, see the Our Roots website).

- The German-American Colonization Co. was founded in 1906 by John Steinbrecher to bring Germans from the US to Canada. The company sold over 100,000 acres of farm land (1910), located 400 homesteads in the Stettler District in Alberta and developed subdivisions in Calgary (Source: Settlement history of “the Germans” in Calgary between ca. 1900 and 1914, University of Alberta.)

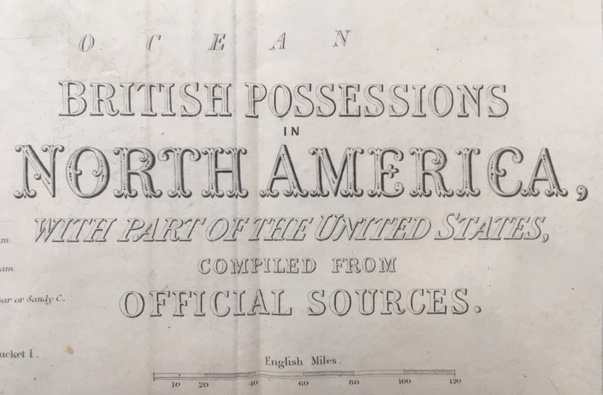

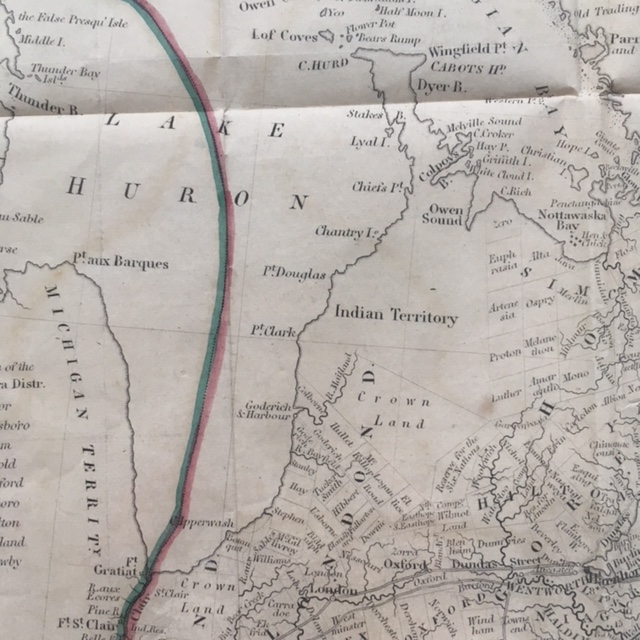

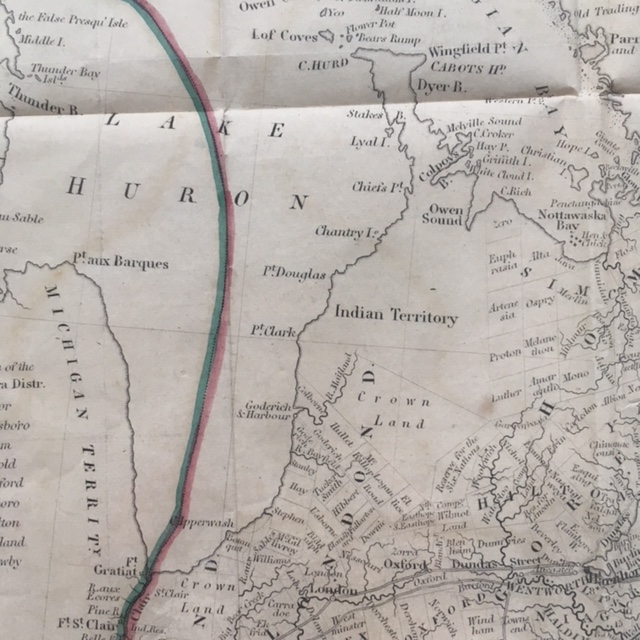

A few weeks ago I was gifted an 1846 map of Upper and Lower Canada. The title: British Possessions in North America. It is a map that reveals the initial city plans for Montreal and Quebec city, the division of land for townships, and remaining “Crown Land” and “Indian Territory”. The purpose of settlers–of whatever their descent–is to colonize the land; in 1846, or the early 1900s, it was to claim it for the British Crown.

As we Europeans arrived, we were part of Canada’s efforts to cause harm to Aboriginal people.

As we Europeans arrived, we were part of Canada’s efforts to cause harm to Aboriginal people.

As we Europeans arrived, we were part of Canada’s efforts to cause harm to Aboriginal people.

The first words of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada:

For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal people to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can be best described as ‘cultural genocide’.

Physical genocide is the mass killing of the members of a targeted group, and biological genocide is the destruction of the group’s reproductive capacity. Cultural genocide is the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.

In its dealing with Aboriginal people, Canada did all these things.

Source: Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1, (p. 3).

I don’t like to think that I have caused others harm, yet I must acknowledge that I, and my European culture, have caused harm. My people were part of a wave of settler immigration to colonize Canada. This is my cultural lineage, and it is a lineage that belongs to European culture resident both in Europe and North America.

Commitment to not cause harm

I am a fourth generation settler in Treaty 6 Territory. I am part of the settler culture that colonized Canada generations ago, and in addition to this I enjoy privileges of being white. (I have a great-grandfather who stopped speaking Norwegian so his progeny could easily assimilate. He noticed that by speaking perfect English and being white, we would “fit in” with dominant society.)

In Canada, we settlers are growing into our understanding of what this means; we are just starting to reconcile how this changes our sense of personal identity. We have caused harm and will continue to cause harm if we are not able to respond (i.e. be response-able).

I arrived in Germany pondering Pema Chodron’s five precepts that form part of a commitment to not cause harm (Living Beautifully with Uncertainty and Change). My summary:

- On protecting life—awareness of ways to cultivate nonaggression and compassion, rather than cause suffering with the destruction of life.

- On respecting what belongs to others—awareness of ways to protect the ‘property’ of others, rather than take what is not offered.

- On not harming others with sexual energy—awareness of ways to nurture love and respect for all beings, rather than cause harm with unwanted sexual energy – to myself and others.

- On mindful speech—awareness of ways to speak truth, rather than gossip, slander, lies, idle speech, words that create division or hatred.

- On protecting body and mind—awareness of ways to be open to all beings and to life itself, rather than engage in things that diminish my inner strength and flexibility.

The legacy of residential schools in Canada is one of intergenerational trauma for Aboriginal peoples. There is another legacy for settlers to live into; I call it intergenerational responsibility. I can take responsibility–on behalf of myself and those before me–for having caused harm and to work to not cause harm.

It takes courage to accept, without defense, that we did not protect life, that we took what was not offered, that we caused sexual harm, that we created hatred toward Aboriginal people, that we were closed to appreciating a way of life different to our own. It takes courage to accept that this is still happening.

It takes courage to accept, without defines, that we did not protect life, that we took what was not offered, what we caused sexual harm, that we created hatred toward Aboriginal people, that we were closed to appreciating a way of life different to our own. It takes courage to accept that that is still happening.

A first step for colonizers: assume a stance of intergenerational responsibility.

Intergenerational responsibility

My trip to Germany involved several days at a retreat center with a group of mostly Europeans, either resident in Europe or of European descent (a few of us from Canada and the US). The retreat posed a challenge to me when we started our time together with a Lakota sweat lodge ceremony.

The authenticity appeared clean to me, with the local German hosts having spent decades learning the ceremony with the Lakota people from North America—with this I have no quarrel. (This was not an example of Winnitou-like German fascination with North American Indians). It took me a while to figure out what was bothering me, careful not to step in and speak on behalf of anyone, in particular not on behalf of North American Aboriginal people who are fully capable of speaking for themselves.

What I figured out was this: there was a lack of reciprocity in this sacred exchange.

The offer of a cultural ceremony from another culture is a sacred exchange that demands some form of reciprocity; in this case, this exchange must include acknowledgement of the efforts we, as Europeans, made to eradicate that very culture. This would have involved naming what we Europeans have taken that is not ours to take. We:

- Took land

- Took art

- Took sacred practices

- Took language

- Took children from families

- Took hair off children

- Took lives of children

- Took culture

Without acknowledgement of what we have taken, we continue to take.

I’ve come to understand that when a gift is offered, the spirit in which it is received and shared matters. My German hosts do not live in Canada, where Truth and Reconciliation is beginning to run in our veins. They are not aware of the harm caused to North American Aboriginal people by us, Europeans. As a result, the ceremony was offered without acknowledgement of harm, which meant the ceremony was received, by participants, without knowing that their very culture organized itself and went to great lengths to eradicate Aboriginal culture in North America.

Participation in such a ceremony comes with an obligation to understand that our European culture attempted cultural genocide.

Participation in such a ceremony comes with an obligation to understand that our European culture attempted cultural genocide.

I write as a European-settler, making an observation about the historic relationship between Europe and North America that is still present today, perhaps helping people of European lineage, residing both in Europe and North America, to see this story more clearly. We share the same lineage and the same colonial pattern regardless of which continent we now call home.

In the moment, at the retreat, I cobbled together some of these thoughts. It was difficult for people to hear, because, of course, we don’t like to hear that we have caused harm to others, but we need to be courageous enough to hear it. If we can’t hear it, then we won’t be receptive to reconciling ourselves with new truths that will change how we think about ourselves.

For some of my colleagues, this seemed like a crack they wanted to open. For others, a quick look and then a desire to look away. And for some, no desire to look at all. All of these responses are normal, for there is only so much rocking we can take.

The challenge we face is thinking we are looking when we are not. A blanket of love and fascination for the spiritual practices of Aboriginal people can serve as a defense: I love it, therefore I can not possibly be causing harm. As people of European lineage, if we are not accepting our story of attempted cultural genocide, we are causing harm. We are propagating the bliss of ignorance. We are taking culture. Love comes with listening, whatever it takes, to the hardship we, ourselves, have caused.

As people of European lineage, if we are not accepting our story of attempted cultural genocide, we are causing harm. We are propagating the bliss of ignorance. We are taking culture.

This matters because the consequences of our taking—the harm—continue. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has documented the legacy of this colonial relationship:

- Overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in care

- Educational and income gaps

- Erosion of language and culture

- Staggering health challenges for Aboriginal people

- Overrepresentation of Aboriginal people in prison

- Denial of justice

- Overrepresentation of Aboriginal people among victims of crime

Harm continues.

Now is not a time to pretend that our love and affection for any practice or ceremony from another culture—as participants and as hosts—is enough. Now is a time to dig deeper to find what the use of the practice means, to find the sacred exchange and enter into that exchange.

Now is not a time to pretend that our love and affection for any practice or ceremony from another culture—as participants and as hosts—is enough. Now is a time to dig deeper to find what the use of the practice means, to find the sacred exchange and enter into that exchange.

We are a global culture, with colonial behaviour and residue everywhere. I embody European colonialism, even when I didn’t know it. I sense this: as I have lost track of my European lineage in Europe, Europeans have lost track of their colonial lineage in North America and around the globe.

There is much to heal when it comes to colonial and indigenous facets of humanity, and healing will only take place if we, of colonial bent, are:

- Ready to hear about harm

- Receptive to a shaken sense of identity

- Willing to step into a relationship of reciprocity

And along the way, we must strive to notice what we take, large or small, particularly when the culture we are potentially taking from is working to reclaim itself from us.

In my patch of the world, I recognize that I have a lot to learn with the Aboriginal people who welcomed my family to Treaty 6 territory four generations ago. Waves of newcomers arrive, all accommodated with unimaginable grace. A sacred exchange is underway, even if we don’t acknowledge it. We have a lot to reconcile.

A sacred exchange is underway, even if we don’t acknowledge it. We have a lot to reconcile.

RESOURCES

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Report

- Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 Origins to 1939, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 1.

- Canada’s Residential Schools: The Legacy, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume 5, retrieved at on January 10, 2018.

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

German and Norwegian Immigration to Canada and Alberta