It was a tense part of the meeting, when the neighbours were challenging city staff about who the city was going to invite to an upcoming meeting. It was one of those moments when I’m quietly telling myself: this is tricky, so make sure you say the right thing or this is going to go off the rails!

(Long story short: residents have lobbied for years for city hall to take action. City hall is now taking action and a small team of city staff met with a group of residents to update them and plan how to engage the rest of the neighbourhood.)

Who are you going to invite? Just the residents? Why should others have a say if they don’t live there? Property owners or everyone who lives there? What about developers from the outside? What about developers from the inside? What if the voice of outsiders drowns out what residents have to say? How will we know who is saying what? If everyone was mixed together in a room, residents and outsiders, how would residents be heard?

If everyone was mixed together in a room, residents and outsiders, how would residents be heard?

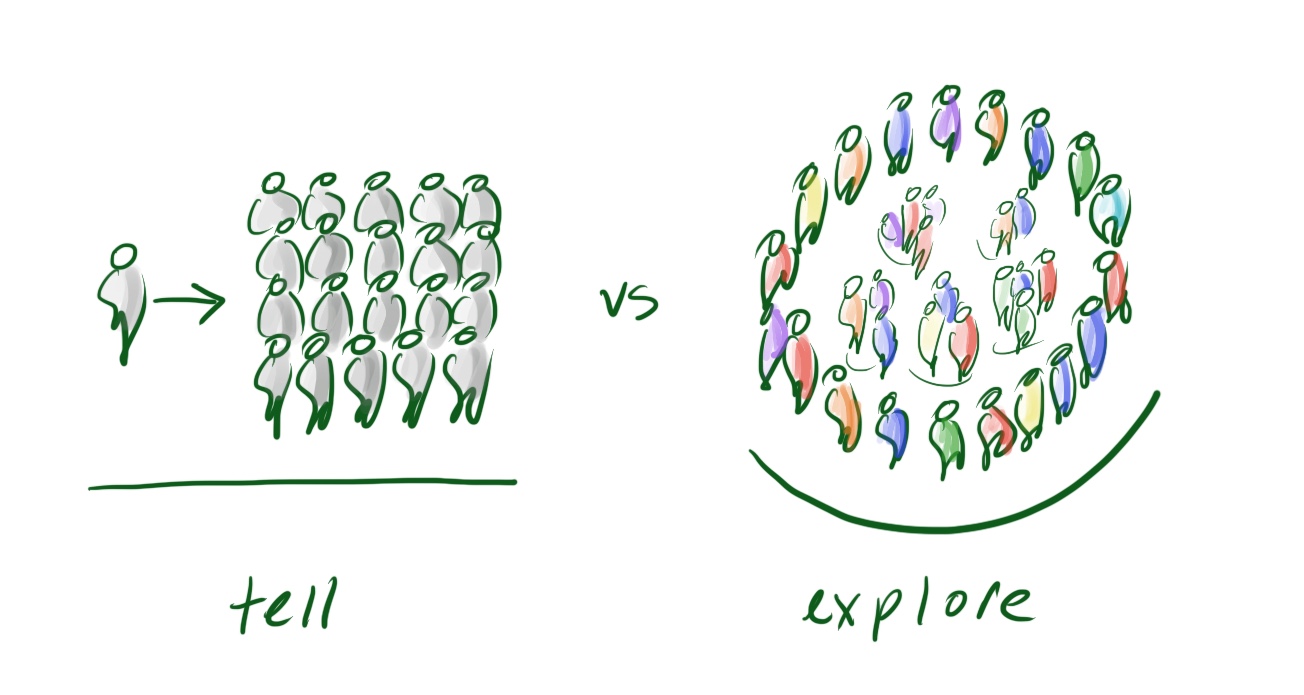

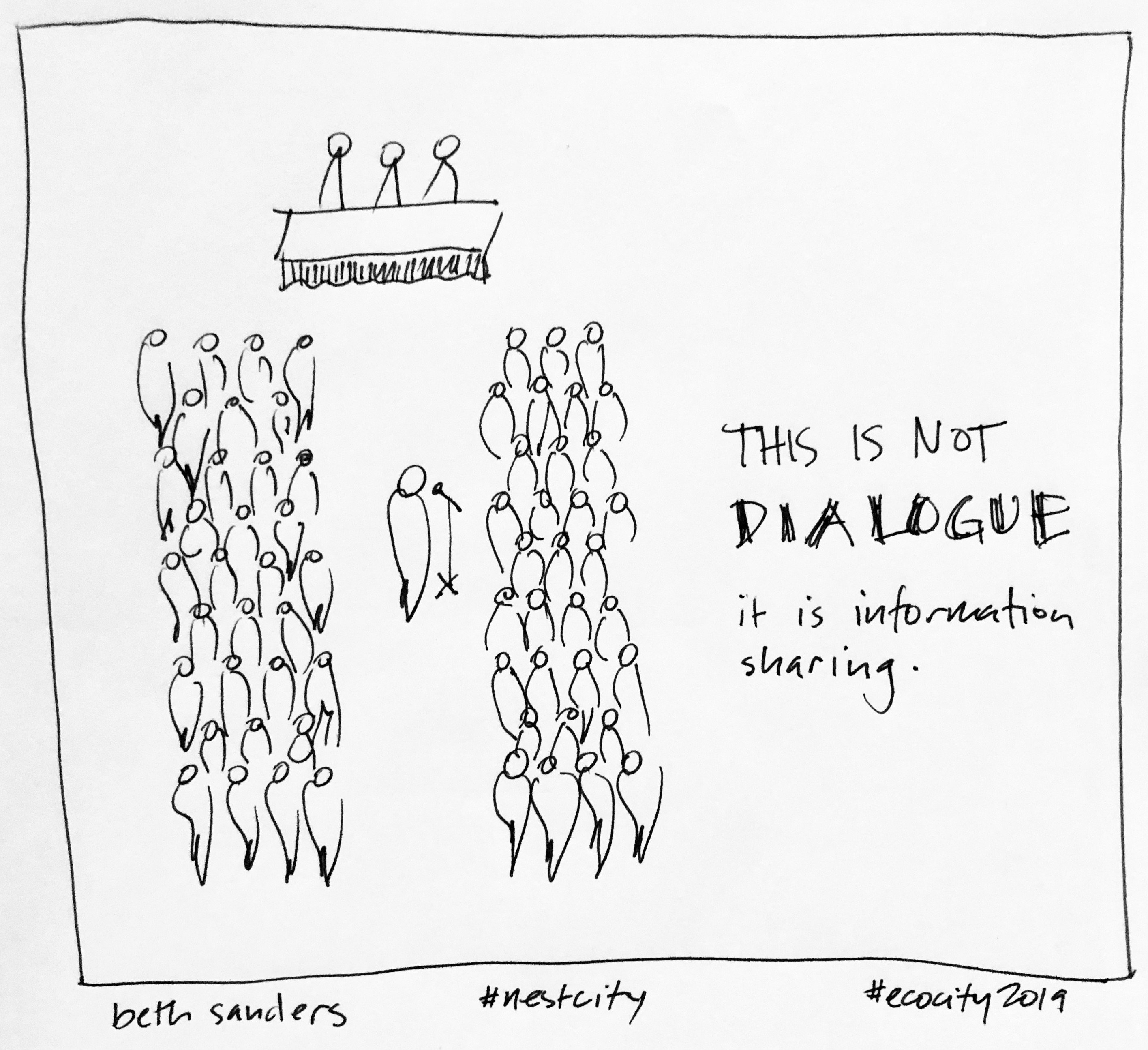

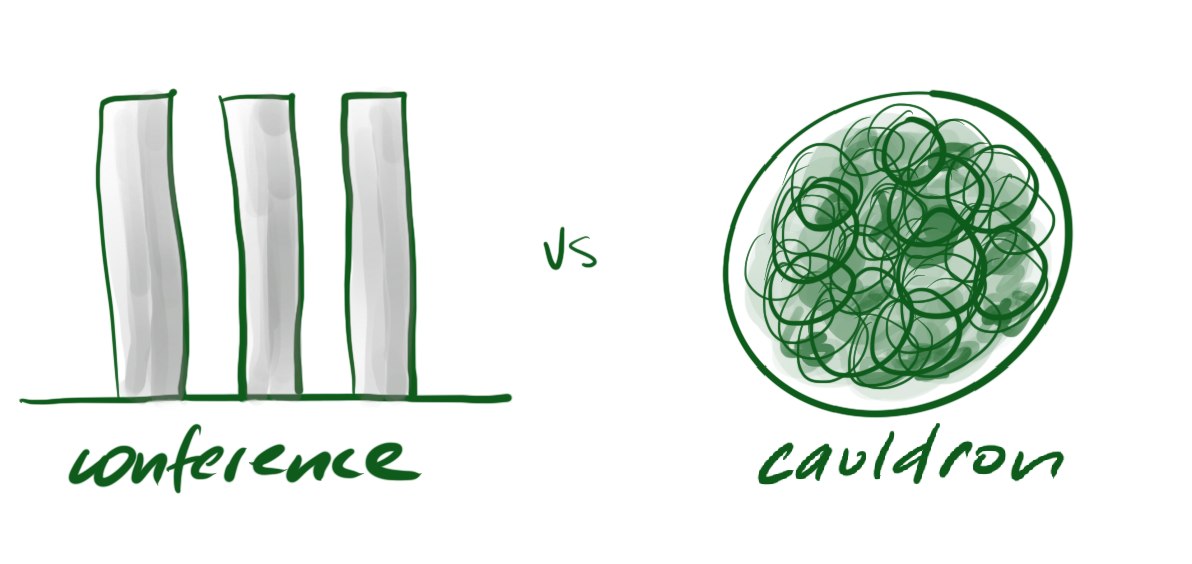

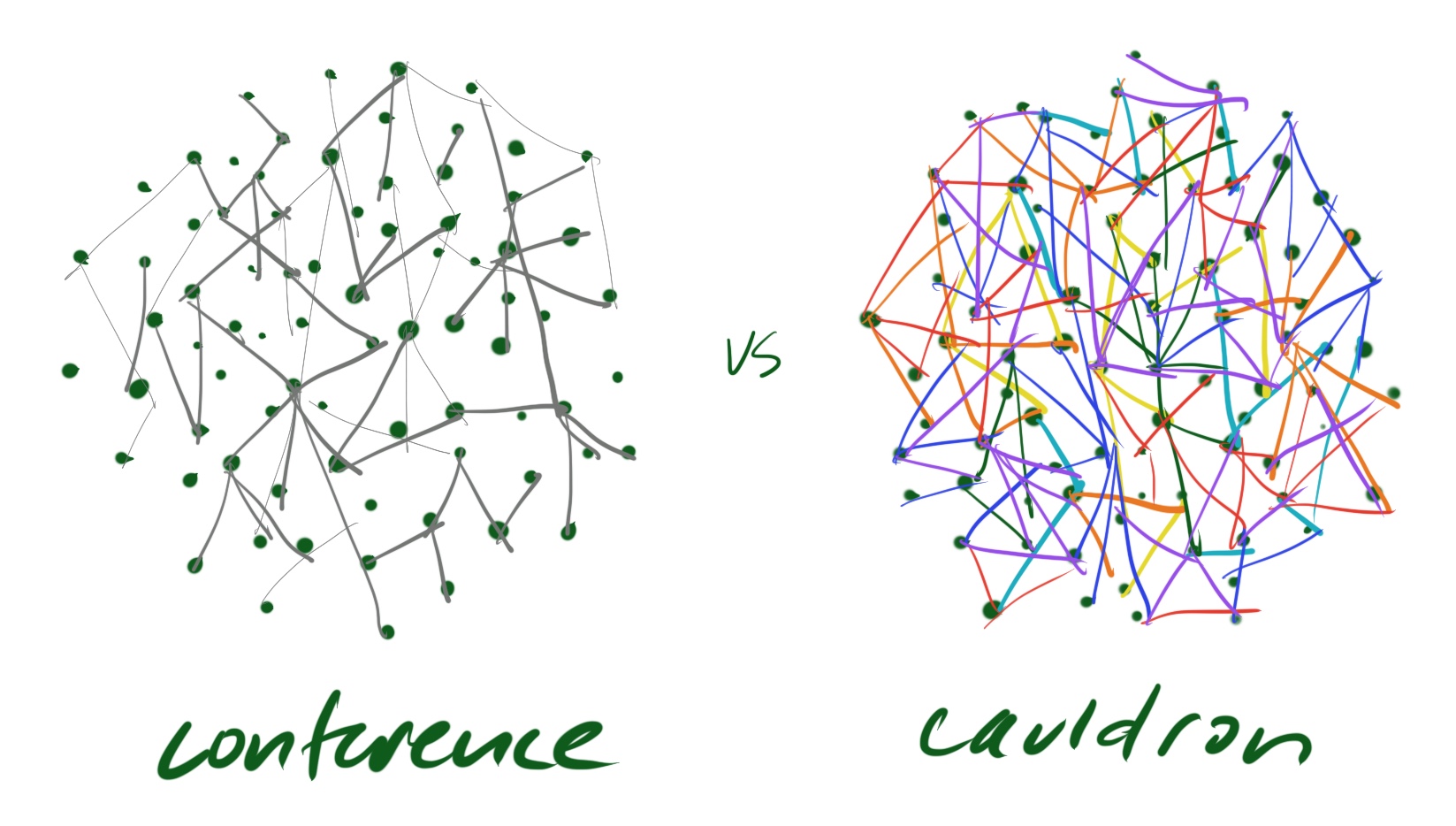

One resident kept asking the sticky question: who are you going to invite? The group had a long conversation about how to have many voices in a room, have them be in conversation with each other (rather than a line-up of people at a microphone), and distinguish who said what. Again the sticky question: who are you going to invite? To clearly hear the voice of residents, then only residents could be in the room.

She just wanted to feel heard.

And when we heard that, we found our way. We identified a means to both hear local residents and invite the wider community that felt good. It took us a bit of time, we had to work through the discomfort of different opinions, but we landed on something that residents felt good about, and city staff felt good about.

They heard each other. They accommodated each other.

10 days ago a trio of wicked communications and marketing brains (read friends) gathered in my living room to help me put together promotional material to promote me and my coming book, Nest City. I was very uncomfortable being the center of attention. I was very uncomfortable talking about how to actively make myself more visible.

With supportive friends, I relaxed into being hosted, rather than being the host of the conversation. One served as a scribe and helped organize what I was saying so I, and we, could see it.

They asked me the tough questions that I often ask them. They relished “Bething” me, putting me in the hot seat.

With their challenging support, two big realizations surfaced:

- It is time to come out of hiding.

- I am well conditioned to put myself in the background.

I have been writing in hiding. I have a book that I have been working on for 13 years that few people have read. Since 2009 I have posted 434 blogs (this is the 435th) and the Nest City News started a few years ago. The readership of public writing is loyal, but not huge. (I love you dearly.)

I don’t “toot my horn” because I’m well trained to not do that. The inner critic in me is active.

I don’t “toot my horn” because I’m well trained to not do that. The inner critic in me is active:

- Only people who are full of themselves promote themselves

- You don’t have anything worthwhile to say

- Don’t dream big because it won’t come to pass anyway and you’ll end up heartbroken

- No one can actually do the work they want to be doing, so why should you be any different?

- No, no, don’t put yourself out there, it’s too risky

- Don’t get involved in social media, you don’t have the stomach for it

- The best and safest place for you is in the background

- You’re not smart enough for people to listen to

- You don’t have anything to say that people want to hear

- Who do you think you are?

- Your writing is awful.

I feel like this inner critic voice in my head is not me. But it certainly works hard to run the show.

When I am with a group of people, I “hear” things others don’t hear. With the residents and city staff the other night, when we were talking about who to invite, I heard that what was most important was for residents to feel heard. If I wasn’t in the room, it is possible that that understanding might not have been reached and the tension may have brewed into blockage, leaving the shared project on rocky ground.

When I am with a group of people, I “hear” things others don’t hear.

I hear how people misunderstand each other. I help them find clarity in what they want to express, and speak it in ways others can hear. I support people to hear the other, even it is uncomfortable to do so.

At times, I also hear what is happening in the room when nobody else knows it is happening. I can sense into “the thing” that is unsaid, and I’m willing to say it.

I notice patterns in our behaviour that keep us from being our best selves, and I design conversational processes that erode those bad behaviors. I notice patterns in the complexity of how cities work that help me (and clients) navigate the systems of the city.

I love to create social habitats in which information, or feedback, is received—even if it is hard to hear. Most importantly, I love to do this when it involves ways to improve our cities.

I’ve just come out of hiding a bit. Just now.

I’ve named two things that are my essential work, that I both love to do and clients want to do with me:

- Create the conditions for people to hear each other.

- Navigate complex city systems.

I’ve said this out loud, here.

What’s coming is a new website with a new look and feel that puts me, my work and my writing out front. I will continue to write to you, but it will come your way with a new look, under a new name. The “Nest City Blog” will turn into “Beth’s Blog”. The “Nest City News” email newsletter will turn into “Writing From the Red Chair”.

I expect to write faster, which means more frequently.

I expect to have more readers.

I expect to have readers that appreciate what I offer, and readers that don’t get me. I will look for healthy criticism and put negativity aside. I will appreciate the appreciation.

I expect to have relationships with readers, not just clients.

I expect to enjoy putting myself out there, being bigger.

I expect to be in more conversations with people who are listening for what is in hiding, in self, others and our cities, and welcome both the challenges and the joy of hearing, of revealing rather than concealing.

Welcome both the challenges and the joy of hearing, of revealing rather than concealing.

What are your practices to hear what is hiding in you? In others? In your city?