A city that embodies courage, invention, cooperation and openness encourages its youth to leave the city. In heeding the call to adventure they are furthering their own growth and development and, potentially, the growth of their city as well. And if we do two things — encourage their journey and are receptive to the changes their departure and return will bring to us — we are helping our city evolve along with their adventure. We who are left behind are on the journey too.

We who are left behind are on the journey too.

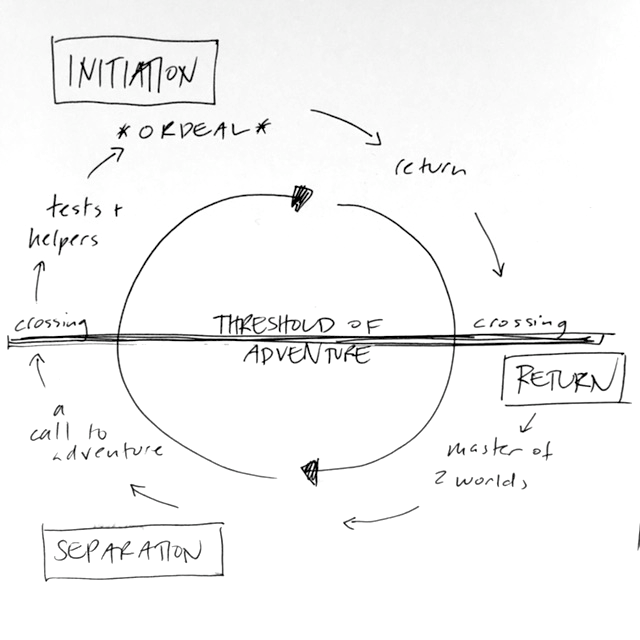

Joseph Campbell identifies three elements of the hero’s journey (see part 1 for more): separation, initiation and return. The hero responds to the call for adventure and separates herself from her everyday world, she undergoes a series of events that test her and a grand ordeal, following which she returns to her community with new insight. It is a substantial personal journey for the hero. It is a journey she must make alone but never without relationship to community; she separates from her community and she returns to her community.

Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey is an archetypal human journey that pervades the myths of all cultures, in their stories, symbols, religions and art. Today we no longer pay attention to the journeys of our own people, but rather watch hero stories on big and small screens, fiction and nonfiction alike. We watch without stopping to make sense of what these stories mean for us as citizens and as cities. We do little to notice, let alone punctuate, our own adventures or those of people around us.

The role of community in the hero’s journey is significant and we have some choices to make. When youth leave to embark on their adventures, do we notice? Do we celebrate them? Do we let them know that they will experience tests and hardship and will be welcomed home when the time comes? When they return, do we notice? Again, do we celebrate them? Do we pause our busy lives and listen to their stories, find ways to incorporate their insights into our lives?

The community-hero relationship

There are three principles embedded in the community-hero relationship. First, as a community we choose to help or hinder the hero’s journey but we are not able to stop it because the call to adventure is strong. Second, the hero’s community is part of the adventure too. Her community is impacted by her desire to go, her departure, and when she returns changed, the community-hero relationship will have to continue to change. Third, this is a community relationship with the hero—its not up to one or two of us to tend to each hero. Community members play varied roles in various heroes lives at various points of time for various lengths of time. It’s an unmappable, unknowable web of community support.

While the hero cycles through a series of stages in Campbell’s journey, the community has similar choices and states. At separation: fight or allow. At initiation: resist or support. At return: disengage or engage.

We improve the resilience of our cities by encouraging youth to leave – if we stay in relationship. Some of us will be tuned into the whole adventure of the hero, others of us will have snippets of roles in various heroes journeys and all of this serves well because together, as a community, we are in relationship. Collectively, we need to edge into consciousness that we need to be in relationship with the hero before her adventure, and responsibly guide her into the unknown. We need to be in relationship with her during their adventure, and serve as helpers and allies from time to time. (Everyone needs a helper or few when times are tough.) We need to welcome her home and provide support as she bridges the gap between the mysterious world of adventure and the everyday world to which she has returned. We need to be open to hearing what she has learned and open to being changed by what she has learned.

No single one of us will have a monopoly on supporting the hero; it is only as a community that we will. For my 19-year-old who is moving to Toronto next month, many of us have supported getting her ready: parents, teachers, extended family and friends. While she is on her adventure, people I can’t imagine will serve as helpers and allies, and others yet will challenge and test her. She may return to live in Edmonton, or she may not. An even wider community, perhaps a whole new city, will hear her story of adventure on her return. While I will make myself available to hear her stories I expect that others will hear her too, wherever she finds herself. And I will do the same for heroes who find their way to Edmonton.

The challenge for community

The challenge is that for most of us one of two things has happened: either we have not yet responded to the call for adventure or, if we have, we did not experience a community that explicitly sent us and welcomed our return, offering support and changing along with us. This means that we do not know how to do this work, how to support each other in ways that allow and amplify our conscious evolution.

We do not know how to do this work, how to support each other in ways that allow and amplify our conscious evolution.

We have lost track of this simple pattern in our lives: separation, initiation and return. In today’s cities we lead busy lives that pull us simultaneously in many directions. We generate so much information for us to pay attention to in the “outside world” that we miss the inner information that informs us about who we are and what’s going on in our lives. We distract ourselves from ourselves and we miss our own plot. We miss the plot of our own personal adventures as well as our cumulative and collective adventures.

There’s a transaction between a city and its young people that can take place at many and all scales, should we choose. In friendships and families, in neighbourhoods and organizations, in cities, a nation, or a planet of cities, all we need to do to start is notice the transitions (separation, initiation, return) that take place when they take place. Its not sufficient for the hero to know this—the community/city needs to participate. The community-hero relationship is about our own becoming.

The community-hero relationship is about our own becoming.

The transaction

Here’s what I have found at the heart of my alarm at my city wanting to keep youth here, in the name of courage, invention, cooperation and openness: for cities to benefit from the young heeding calls for adventure, the hero does not need to go back to “her” city.” It isn’t about one single city, it’s about all cities and their interconnections.

Our youth, heading out on their hero-adventures, are a means for cities to create interrelationships, an essential element of resiliency. Supporting youth to leave, have their adventure and return means we are supporting the interrelationships, and since more interrelationships means more resilience, we are improving the resilience of our cities by supporting youth. When youth leave my city they go to other cities and my city receives other youth when we are open to them. When we are courageous enough to gift our youth to the cities of the world, we receive hero-adventurers in return. This is a vital transaction for my city—and all cities.

When we are courageous enough to gift our youth to the cities of the world, we receive hero-adventurers in return. This is a vital transaction for my city—and all cities.

This is a truth we all know: to best see our place in the world we need to experience other places. In doing this, we recognize the things we most appreciate about our place and grow ideas about how to improve our place. This is what our hero-adventurers are doing for us. And when they don’t physically return, they are still doing this work in ways we will not see.

If it hero makes her way home to her city of origin, welcome her home and listen to her stories and involve her in making the world in your city a better place. In today’s world there are other forms of return for us to contemplate. She might only visit from time to time, or rarely, in which case we welcome her and celebrate. We can also claim her as ours, appreciating and learning from her contributions, and making our gift to the world explicit.

Our hero-youth are the champions of what we are becoming. A courageous city will encourage our young to leave and explore, from a place of openness that allows us to learn along with them.

A courageous city will encourage our young to leave and explore, from a place of openness…

Two related posts:

When I spend time out on the land, and I listen, it has things to tell me. Last month, while hosting Soul Spark with my friend and colleague Katharine Weinmann, I ventured outside to be on the land a bit before we got started.

When I spend time out on the land, and I listen, it has things to tell me. Last month, while hosting Soul Spark with my friend and colleague Katharine Weinmann, I ventured outside to be on the land a bit before we got started.