It doesn’t feel good when people in your city scream at you. Last month I was on my bike, on a downtown street, making my way to the new bike lanes a few blocks away. A truck driver yelled at the top of his lungs: USE THE F$&#ING BIKE LANES!!!

Only three days before this happened, I jumped on a bicycle, rode 15 minutes on streets of various sizes that accommodated many modes of transportation — bicycles, pedestrians, scooters, cars, trucks, buses and trams – to get to Utrecht’s Central Station in the Netherlands. I got on a train with my bicycle and in 30 minutes was emerging from Amsterdam’s Central Station with a map in my pocket and two hands on handlebars, to make my way on bustling unfamiliar medieval streets to Park Museumplein and the surrounding sights. I was in the busy throng of people moving in many ways through the city.

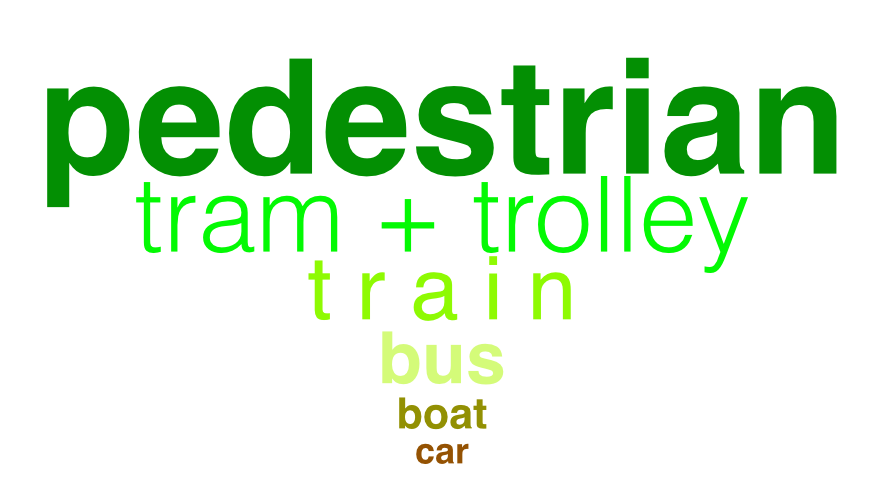

There were choices about how to move in Utrecht and Amsterdam. I could choose to move by car, on foot, on a bicycle powered by me or electricity or gas, or by bus, tram or train. The city is designed for choice and the inhabitants live the choices they have made available to themselves. There are people who choose cars. There are people who choose bicycles or scooters. There are people who choose buses, trams and trains. And there are people who choose it all. Most importantly, those choices are available just about everywhere. There is significant public investment made to do this, in the streets and even bicycle parking lots. (Check out this article about the Utrecht Central Station bicycle parking facilities for 22000 bicycles.)

The inhabitants live the choices they have made available to themselves.

There are sensible separations that are responsive to scale and speed, always with a the larger intention to allow choice. There are no bicyles on highways, but bicyles can be on trains or you can ride your bike between cities. In the city proper, bicycles are everywhere and the city is made for it. Make a sidewalk a bit wider, paint it a different colour and there’s room for bicycles on a busy street of any size. On a small local street, bicycles are on the street with the cars. Intersections are made for all modes of transportation and while messy compared to the simplicity of an intersections only for cars, it works perfectly. All people, regardless of their chosen mode of transportation, exhibit care and look out for each other. That’s how it works: accommodation.

All people, regardless of their chosen mode of transportation, exhibit care and look out for each other. That’s how it works: accommodation.

Back in Edmonton, in North America, my experience is a startling contrast. In one 20 minute ride into downtown and back home I realize:

- There is no place for me to be. I have to choose to be like a car and be on the road or choose to be like a pedestrian and be on the sidewalk. My ride starts on a quiet street so I choose the street. When the car traffic gets busier I ride on the sidewalk. I don’t like to do this.

- The new bicycle path does not go to where I am going, so I choose not to use it, despite wanting to support the public investment.

- Friendly drivers don’t know what do to. On a quiet street I choose to ride on the street. At an intersection where I have the stop sign, a driver stops and waves me on. This is nice, but she would not stop like this if I was a car.

- The streets with new bicycle lanes downtown do not go where I am going. As I travel through downtown, I pass cross streets with bicycle lanes. I could move south, away from where I am going, to be on a bicycle lane, but that is out of my way and doesn’t feel right. I stay on the street because there are few vehicles.

- There isn’t a place to park my bike. I arrive at my destination, Edmonton Tower, for a meeting with City of Edmonton colleagues. There is room for 12 bicycles to park and it is full. I ask, again, for the security personnel to pass along to the management that more facilities for bicycle parking are needed.

- Some drivers are ANGRY. On my way home, I decide to go out of my way to use one of the new bicycle lanes, so there is one more visible cyclist using this investment. On my way there I find myself on a narrow street with no sidewalk because of construction. This is when the driver screams out his window: USE THE F&%$ING BIKE LANE!!!! I was in the only place I could be to get to the bike lane.

- Another driver is ANGRY. A bit later, while crossing a street (on the street like a car) a driver honks his horn at me. I look (maybe it’s someone I know?) and see him moving his fingers as if I should be walking across the street. I shrug my shoulders. He honks again. Longer.

This is not the Edmonton I want to be, where the power of the car dominates the choices of its citizens. But lets be clear — we give the car its power. It is our choice. We attach ourselves to the car life and feel threatened by the choices that are available to all of us. The car brought us a sense of control, an ability to go where we want when we want. This is, however, a form of power over people who by choice or need do not use a car. More of us have control – in the form of choices – if more of us have choices about how to move around in our city.

To be friendly to all modes of transportation, this is what I envision for Edmonton:

- Various modes of transportation are available to all citizens. This means both physical access (is the infrastructure there) but also the financial means of the user. This takes place both on the street and also across the city. (Note – street here means the entire public right-of-way.)

- Various modes of transportation are available to all citizens EVERYWHERE. It isn’t about choosing specific places where bicycles and buses and trains will go. It’s about choosing specific places where bicycles will not go. Bicycle infrastructure is cheap and easy. Just do it. This takes place both on the street and also across the city.

- There are clear rules for how street users behave because there is a clear place for them. Pedestrians, cyclists and vehicle drivers all have their own place to be on the street and know what to expect of each other. The bicycle is not a pedestrian or a car or a train, but since we don’t have a place for bicycles, we have unnecessary conflict between street users.

- All street users are courteous and patient. It’s easy to navigate a street for cars or a street for pedestrians. It’s more complicated to navigate a street for cars and pedestrians. It’s more complicated to navigate a street with cars, pedestrians, bicycles, trams and scooters, but it is doable. Millions of humans live this in various parts of the world. The choice is ours, but it will take courage to behave in ways that are courteous and patient both as we recreate our city and figure out how to relate to each other and our city differently.

There is hard work ahead for us in North American cities. We have a built form that serves the car and we need to shift it to include other ways of moving. This is a gargantuan task, but is not the biggest task. The biggest task is to be civil and friendly with each other while doing the difficult work of making cities that serve citizens well.