As for any city, the shape of St. John’s is derived from its geography, its purpose, the activities within and in connection to other cities (see part 1 and part 2). There was no master plan for St. John’s to become what it became. The shape and character of St. John’s did not take place because of a single dream, or a single person, or even a single authority. In times of colonial expansion, the geography of St. John’s provided ice-free shelter at the Eastern edge of North America. The settlement was established where it made sense to be.

In the end, colonial authorities and the people living in St. John’s gave it its shape. Military personnel, governors, port authority officials, businessmen, church leaders, servants and the patterns of how families met their needs all shaped the city. They organized themselves to make sure they had what they needed to survive and thrive as individuals, as a settlement and as an Empire. Collectively, they knew what it would take to run the fishery from the port of St. John’s and they did it.

St. John’s continues to adjust and organize as conditions change; it keeps what it values and moves on and away from what it does not:

- The Rooms, St. John’s seat of cultural identity that provides public access to history, heritage and art, overlooks the harbor from the site of its seat of military identity: Fort Townshend.

The Rooms, overlooking St. John's Harbour (http://cruisetheedge.com/galleryimages/9%20The%20Rooms.jpg) - The fish flakes no longer surround the harbor, but the unplanned city survives as a cultural hub and tourism asset. It is woven into today’s St. John’s. The public access to pathways on Signal Hill from Outer Battery Road passes over a home’s deck, less than a metre from the home’s front door.

- The St. John’s Port Authority continues to serve local, regional and international trade requirements. It’smission is to provide reliable, economic and efficient port services in support of Canadian trade, fostering regional economic development and serving Newfoundland and Labrador’s distribution requirements.

Purpose and Life Conditions

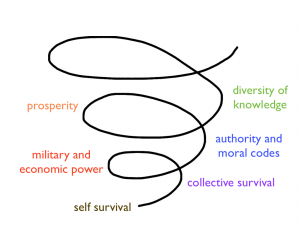

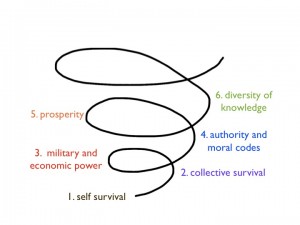

Life conditions vary from city to city, each adjusting and organizing itself – and adjusting its purpose as appropriate. The St. John’s example highlights five distinct purposes (1-5 in Figure 1): individual survival, collective survival, power, authority and prosperity. (More on this spiral in Chapter 3 – The Thriving Impulse.) Each of these has its own trajectory that shapes St. John’s over time. In practice, each of these purposes involves integration of the local needs of individuals and the city, with relationships with other cities – a necessary condition for the city’s survival that is clearly still a focus for St. John’s.

The St. John’s example illuminates principles about how cities fundamentally take their shape:

- The purpose of a city guides its form and shape

- The purpose of a city, as it adjusts and shifts, becomes diffused

- As the purpose of a city becomes diffused, its purpose expands to serve the diffused needs

- As the purpose becomes more diffused, decision-making is made by a wider group of individuals to accommodate this expansion

- All of the above occurs within the context of the city’s life conditions

St. John’s was not planned to be what it is today, but it is certainly not unintentional. Is that enough to say that it is unplanned? It did what it needed to do in each stage of its development. Does ‘planning’ mean that it should have done more than respond to the life conditions at each stage of development? Or are there degrees of planning that correspond to evolving city purposes.

The overriding purpose of a city is to integrate the needs of its people, with its context, to create a habitat in which people will survive and thrive. This is the fundamental context in which we all work. And a profession (new work) emerged among us to help us collectively accomplish this: city planning.

‘Planning’ a city is simply an activity that supports our collective work to organize ourselves to ensure our habitat serves us well. The activity of planning emerged when our life conditions required additional order; Our planning activities will adjust as we need different kinds of order.

“Is an unplanned city unplanned?” will conclude with a description of the evolution of the role of planning and planning practitioners as our cities evolve.

Sources –

Beck, Don Edward and Cowan, Christopher C., Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford (2006), particularly pages 52-56.

Hamilton, Marilyn, Integral City: Evolutionary Intelligences for the Human Hive, New Society Publishers Inc., Gabriola Island (2008)

Sanders, Beth, “From the High Water Mark to the Back of the Fish Flakes: The Evolutionary Purpose of Cities,” Vol 51, No. 4, p 26-31, Plan Canada. Print publication of the Canadian Institute of Planners.