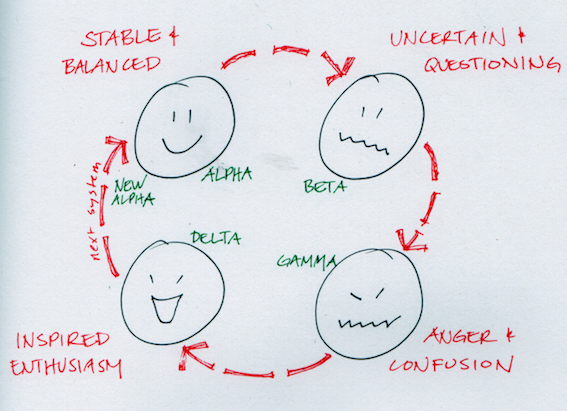

There is great momentum in being busy, being distracted from who we really are and the possibilities we offer the world. The result is that each of us, and the city habitats we create for ourselves, are not reaching our full potential.

Yesterday’s post, performance with purpose, articulated the phenomenon of performance momentum, were we find ourselves caught in a drive to perform. In this state, we lose track of who we are and the inner passion that drives our work. We lose track of the purpose of our work and dismiss the feedback loops that ensure our work is responsive to the needs around us. The result is work that does not move the self, the organization, or the city forward. There is no improvement; which is itself a fundamentally driver to our work.

In the work we do creates our cities, I concluded with two questions:

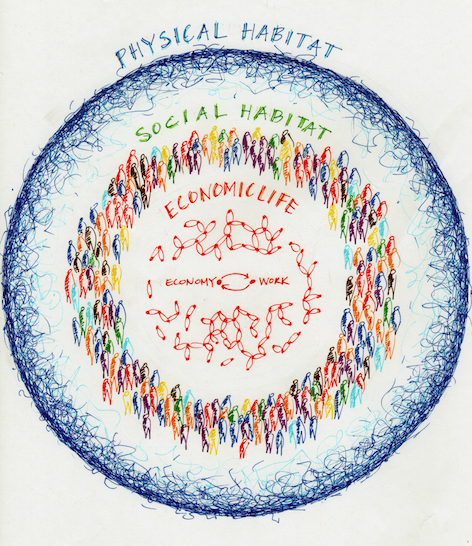

- To what extent is our work, even new work, blind to our changing habitat?

- How would we change how we organize ourselves to consciously choose to create habitats for ourselves that serve our present and evolving needs and desires?

From time to time, it is essential to stop, to pause and have a look at the deeper inner self, the one that wants to be let out, free in the world. As we each allow our hidden self to emerge, our cities will change to serve us better. As our cities improve, they are creating the conditions for us to be better again.

It is hard to stop and listen – and we need to learn how to do this, for self and the city. David Whyte, in The Three Marriages, has this to say:

… anyone who has spent any time in silence trying to let this deeper hidden self emerge, soon finds it does not seem to respond to the language of coercion or strategy. It cannot be worried into existence. Anxiety actually seems to keep an experience of the deeper self at bay. This hidden self seems reluctant to be listed, categorized, threatened or coerced. It lives beneath our surface tiredness, waiting, it seems, for us to stop. Stopping can be very difficult. It can take exhaustion, extreme circumstances on a wet, snowy mountain ridge or an intimate sense of loss for it to happen Even then we can soon neutralize and isolate the experience, dismissing it as illogical, pretending it didn’t count, then turning back to our surface strengths and chattering away in a false language we have built around our successes. Success can be the greatest barrier to stopping, to quiet, to opening up the radically different form of conversation that is necessary for understanding this larger sense of the self. Our very success can be the cause of greater anxiety for further preservation of our success (p, 154-155)._____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.