After a delectable Turkish meal in Inverness Scotland, I found myself contemplating eras of old: a visit to 4000-year-old Bronze Age Corrimony Cairn, the ruins of medieval Urquart Castle and a boat ride on Loch Ness. While no humans today know why the cairn has 11 standing stones, rather than 12, we do know it was purposefully built, assumed for ceremony of some kind. Urquart Castle, looking out on Loch Ness, is likely on the site of an earlier Pictish fort, and it’s more tangible history is as a military stronghold from the 1200s to its ruin in 1692. The English took it in 1296, and it went back and forth between the Scottish clans and the English. At the Urquart Castle visitor centre, the words “fire and sword” are front and center. And then there is the myth of the Loch Ness monster, Nessie, and whether she exists, did exist, or even could have, according to scientific research. The Turkish meal, with my journal beside me, elucidated mystery and clarity.

While the precise details are not known and the castle itself stands (or not) in ruins, the role of Urquart Castle is pretty clear. It is the physical manifestation of power, it’s occupants revealing who is in power. If you are not the ‘king of the castle’ you are not the king. If you are not closely tied to the king of the castle you do not have his protection. If you are not living in it, or tied to who is in it, you are on the outside. And the castle is only looking after those within and their allies.

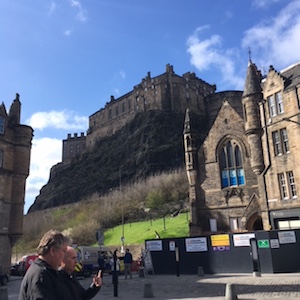

While Urquart Castle now stands in a natural setting on a rocky promontory along Loch Ness, elsewhere in Scotland, in contrast, the setting of Edinburgh Castle is a medieval and modern city. Just like Urquart, Edinburgh Castle is a story of power and sieges. (Have a look at the Wikipedia page on Edinburgh Castle for the details of the ‘Game of Thrones’ power struggles involving Edinburgh Castle.) As I walked along the Royal Mile in Edinburgh’s old town up to the castle, and as I enjoyed the view of Edinburg from the esplanade, looking down upon the city, a question emerged for me about castles and cities: a castle is not made for everyone—is a city?

With a castle and a king or queen, there are physical walls and barriers to keep people in and keep people out. The game is about power, sorting out who is on the inside or outside. The invisible walls and barriers are tangible and clear: if you are of a certain class, gender, age or financial resources, you have your place. Roles are clear and defined with firm protocols and consequences. The expectation is that the lower your station, the less power or influence you have, the least change you can effect. You have to have power to be somebody. A castle is not made for everyone.

So is a city made for everyone? I propose it can be. As we evolve past the turf and territory of castles (whether literal or metaphorical), we move into the experience of the city a shared project: a city that serves citizens well. We can care out in open.

As we evolve past the turf and territory of castles (whether literal or metaphorical), we move into the experience of the city a shared project: a city that serves citizens well.

As a shared project, the making of a city involves all of us and our work, everyone in the city and city region, to make it as we want and need it to be. There is an implicit contract in city life, that my work helps someone, who helps someone, who helps someone, who helps someone who helps you, and vice versa. As our work becomes more and more differentiated, this reliance on each others is how it works; I rely on others to do my dentistry, to make sure groceries are at the store, to make sure I have clean water. If I didn’t rest in this reliance, I would have a very different life.

Like any shared project, it works best if all parties are involved in ways that are meaningful to them. It is an ugly and beautiful process with ugly and beautiful results.

In my city, much like yours I suspect, a significant challenge rests in the acceptance of others’ experience of the city, their experience of the invisible walls and barriers. For example, when working with my city library in the development of a new culinary learning space, they ensured a variety of perspectives about food were in the room to explore how to design the space. There are the people who want to learn how to make cheese or Indian food. There are the teaching chefs who know how to design a space that works for instruction. There are the people who want to learn how to cook for themselves. There are the new local food producers who need a place to work for a weekend. There are the library patrons that need a lunch. There are the people who grow food. There are people who want to gather to share a meal and talk about fun or tough stuff. There is no one purpose of the culinary learning space, for it will be different things for different people. Just like a city is different things for different people.

In a castle world, people in different positions don’t view the world in the same way. This still occurs in the city when power imbalances are in play—it’s just that the walls and barriers aren’t so visible and clear. In my work with people across my city, I notice that we humans find it hard to believe in the existence of barriers named by others if we don’t see that barrier, or experience that barrier. It might be a builder who says the development approval process is onerous, not believed by citizens concerned about new construction in their neighbourhood. It might be the social service agencies who describe the ongoing structural struggles for the city’s poorest families to find appropriate housing and make ends meet and the electorate who has sufficient resources at their disposal so doesn’t see the need to provide assistance.

I notice that we humans find it hard to believe in the existence of barriers named by others if we don’t see that barrier, or experience that barrier.

We humans trust our experience and mistrust the experience of others if it is different than ours. It’s hard for us to imagine and believe. Yet in the city as a shared project, we have to accept that just because I don’t see or experience barriers named by others, that does not mean those barriers are not there.

Making a city that’s made for everyone involves trusting others’ experience of the city.

Making a city that’s made for everyone involves trusting others’ experience of the city. Knowing that the city is castle-like for many, there’s a leap to be made by those of us who have our needs met: to trust and believe what others tell us about their experience. To not argue, debate, deny and resist, but accept.

____

Warning: The reason we find it difficult to trust another’s experience is because it invites their sovereignty, which involves disruption of out view of the world, and might even disrupt our sense of identity. Inviting the sovereignty of others means I will need to let go of things I enjoy from my place of privilege and power.

Under what conditions do you find you are able to trust another’s experience of the city when that experience is different from your own?

I thoroughly enjoyed this since it added an extra to my trip there. Trust is the key to all communal endeavours.

Thanks, Andres. Glad it added another layer to your/our experience in Scotland 🙂