Skip to content

Eventually we realize that not knowing what to do is just as real and just as useful as knowing what to do. Not knowing stops us from taking false directions.

…

If you think you know where you are, you stop looking.

David Whyte, The Three Marriages (p. 131)

We do not seek out uncertainty, or not knowing – let alone purposefully explore it – because it seems to naturally lead to negative thoughts and feelings. If we choose to generate positive-feeling thoughts and beliefs about not knowing, what role would we give to uncertainty in our lives? What would we reveal?

Pondering these questions requires that we stop and listen, to our selves and our city. Noticing what we do not know is a start. Whyte notes that this is purposeful; it prevents us from taking false directions. Noticing what we do not know can be a reality check, keeping us aware of what we do not know when we make decisions, ensuring that we do have the information we need. Noticing what we do not know may lead to knowing more and making better decisions.

Noticing what we do not know may also compel the realization that we can not know more. In some instances, it is critical to know as much as possible before proceeding. In other instances it is not possible to know. I need to be certain that the brakes work on my vehicle, but I do not need to be certain of the route I will take to get my daughter to the mall for new jeans. I just need to know where I am going and have a few options.

In the longer term, it is less and less possible to know exactly what will happen. We live in a complex world where innumerable variables affect the future we create for ourselves. There are many instances where we may never know what we need to know to make decisions today. This is particularly acute as we organize our cities. We do not know what economic drivers will ensure our cities’ success. We do not know what the demographic trends of our cities will be in 40 years. We do not know where our energy infrastructure will look like in 40 years. We do not know if plague will reduce the human population dramatically. We do not know if we will be travelling in space in 40 years. There are innumerable questions as we look at our future that we can answer, but those answers are only placeholders in place of not knowing.

Our curiosity is a pathway into the learning journey we share in our cities. Our curiosity in what we do not know, whether it can be known or not, allows us to deepen our understanding in both our selves, others and our city habitats. To make wise decisions, and to live with not knowing when we can not know, we must be able to be well with self and others.

While not knowing makes us uneasy, we can use not knowing purposefully to:

- Notice what we do not know

- Notice if we need to know more

- Notice if we can know more

- Notice if we can not know more

- Notice the meaning in what we can not know

- Notice the learning in what we do not know

What do you notice?

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

There is great momentum in being busy, being distracted from who we really are and the possibilities we offer the world. The result is that each of us, and the city habitats we create for ourselves, are not reaching our full potential.

Yesterday’s post, performance with purpose, articulated the phenomenon of performance momentum, were we find ourselves caught in a drive to perform. In this state, we lose track of who we are and the inner passion that drives our work. We lose track of the purpose of our work and dismiss the feedback loops that ensure our work is responsive to the needs around us. The result is work that does not move the self, the organization, or the city forward. There is no improvement; which is itself a fundamentally driver to our work.

In the work we do creates our cities, I concluded with two questions:

- To what extent is our work, even new work, blind to our changing habitat?

- How would we change how we organize ourselves to consciously choose to create habitats for ourselves that serve our present and evolving needs and desires?

The answers to these questions, or rather the exploration of these questions, are part of the city’s learning journey. How each of us approaches our work has an impact on our cities. How we collectively approach our work has an impact on our cities. The cities we create, in return, have an impact on us. If we are ‘busy’, missing the clues around us, then our cities will also miss the clues and not serve us well. If we need healthy cities, and they are made by us, then we need to be well for cities to be well. The

development of our cities is a survival skill.

From time to time, it is essential to stop, to pause and have a look at the deeper inner self, the one that wants to be let out, free in the world. As we each allow our hidden self to emerge, our cities will change to serve us better. As our cities improve, they are creating the conditions for us to be better again.

It is hard to stop and listen – and we need to learn how to do this, for self and the city. David Whyte, in The Three Marriages, has this to say:

… anyone who has spent any time in silence trying to let this deeper hidden self emerge, soon finds it does not seem to respond to the language of coercion or strategy. It cannot be worried into existence. Anxiety actually seems to keep an experience of the deeper self at bay. This hidden self seems reluctant to be listed, categorized, threatened or coerced. It lives beneath our surface tiredness, waiting, it seems, for us to stop.

Stopping can be very difficult. It can take exhaustion, extreme circumstances on a wet, snowy mountain ridge or an intimate sense of loss for it to happen Even then we can soon neutralize and isolate the experience, dismissing it as illogical, pretending it didn’t count, then turning back to our surface strengths and chattering away in a false language we have built around our successes.

Success can be the greatest barrier to stopping, to quiet, to opening up the radically different form of conversation that is necessary for understanding this larger sense of the self. Our very success can be the cause of greater anxiety for further preservation of our success (p, 154-155).

It seems the opposite of busy, performance momentum is to pause, to stop. The lure of momentum, particularly if it is full of what we perceive as success, makes it difficult to slow down enough to give ourselves an opportunity to notice the purpose of our work, the meaning in our work and our innermost qualities of who we are individually and collectively.

How do you pause and stop to listen to your Self and city habitats?

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

From 2005 to 2007 I had the best job in the world, full of challenges at a fast pace. I was running the planning and development department for North America’s fastest growing municipality: the Regional Municpality of Wood Buffalo in the heart of Canada’ oil sands. Political, cultural, social, environmental and economic struggles were the norm, and in the middle our municipal government with a little department with few people to do the work that needed to be done. I know now that the whole time there was something bothering me, a little itch that came and went. W. Timothy Gallwey, in The Inner Game of Work, perfectly describes my itch: performance momentum.

Not all movement or action taken in our work actually moves me, or the organization I serve, forward. Gallwey: “There is a kind of activity that most of us are very familiar with that is not done with conscious intent or awareness of purpose. I call it performance momentum.” Most often it is ‘busy’ work, work that makes us look (and feel) like we are doing something of value. We get energized by the adrenalin and even panic to get things done. We get galvanized by the drive to get things done. And we lose sight of purpose and priorities.

I recognize this phenomenon in groups of people and individuals. We each have moments when we have the foot on the gas regardless of whether we have traction, when we assume that having a foot on the gas is always a good thing. We must always check to see if what we do is effective. We need feedback loops and we need to be open to hearing the messages of the feedback loops.

A city, an organization, a person that is intent on doing things – without a clear and conscious purpose – suffers from performance momentum. It could be connected to a need to be doing, or seen to be doing. We collectively create this culture for ourselves and for each other.

When I get caught in performance momentum, I get tired and unable to do the work well for long. Yet stepping out of performance momentum is not a license to not perform. There is certainly work to be done – and work to be done in a timely manner. The catch is knowing if the work taking place is the right thing to do at the right time, recognizing the work’s purpose. It is about working consciously.

I didn’t reach this understanding until I gave myself time and permission to stop and look at what was bothering me – at what and why I was itchy. I started to scratch this itch five years ago, and as usually what happens with an itch, it has become itchier and itchier. My choosing to write and explore is a risk I welcome: I may find relief, or I may find that I set off deeper, longer lasting itches.

So what’s the opposite of performance momentum? Performance with purpose, full of feedback loops that tell us when we are on track. Noticing when we have traction, rather than wheels spinning, is part of our learning journey.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

We limit ourselves greatly when we focus on what we have to fix. It keeps us in the here and now, not the better world we have in mind.

Here’s a scenario. Imagine I live east of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta, Canada. Imagine I dream of surfing the ocean waves, an activity I can not do on the prairies. I dream of getting to the West Coast and the Pacific Ocean on the other side of the mountains.

In fix mode, I will try to find ways to spend time in the water here. I might try other sports, I might make do with windy lakes in the summer. I might make periodic trips to the West Coast to surf from time to time. However, if I really want to fulfill my passion of surfing I need to shift from fix mode to something else. I need to find a way to make it happen.

I am not going to get to surfing life on the West Coast if I am making do with what I have. When I am making do, I put all my energy into making do, not making it to where I want to go. Equally, I will not get what I want if I put my energy into complaining about my current situation either. I will not get to where I want to go pondering why it is that I am not there. To get what I want, I have to shift my attention to what I want, in this case life on the West Coast.

Our cities are no different. We recognize that there are many things at which our cities need be better. We complain about traffic, homelessness, energy consumption, housing costs, pollution, etc. There are endless studies underway to analyze why things are the way they are, and solutions to ‘fix’ the problems we are experiencing. What we are missing is most critical – knowing what our cities do really well right now and what we can do to have more of what works. Without knowing this, we are not in relationship with our city habitat. We are not allowing it to serve us well. (As I write this, I realize that if a city wanted to up and move to the West Coast, it can’t. But its inhabitants can. Cities are where we put them, where we want to be, not the other way around.)

Notice where the energy of the city (or any organization for that matter) is focused. Is it on short-term decisions to make short-term course corrections, or is there a focus on where the city is going, looking out further ahead. When riding a bicycle, or driving a car, if focused on the immediate future the ride is jerky. When we look farther ahead, the ride is wiser, smoother. The likelihood of wrong turns is lessened. The likelihood of hitting a pot-hole is lessened. The likelihood of hitting pedestrians or other vehicles is lessened. We move through the world in a safer, wiser way.

Our choices as individuals and collectives shape the city. In the back of my mind, I always ask, what am I allowing? Am I making room for new possibilities to emerge? Am I making way for what I want, what we want, rather than putting my attention and efforts in conscious or unconscious efforts to have more of the same.

Here is the trick with fixing what’s wrong. First, it puts our attention on what is wrong, rather than what we want. It tricks us into thinking that if we just sort ‘this’ out, things will be right. Sounds a bit like a silver bullet, but it leads us to getting more of the same.

When we put our attention to where we are, we stay there. When we put our attention to where we want to go, we move in a new direction.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

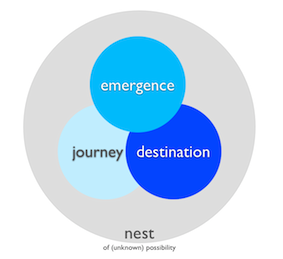

As I reflect on last Monday’s post, A retreat from the retreat, I realize that my experience is a fractal of the city experience. It is a smaller version of the same thing. I had a sense of where I wanted to go, I had some learning to do along the way, and I ended up somewhere that I could not have predicted. It emerged. Whether I organize as an individual, or as part of an organization or at the scale of a city, nation or planet, we are doing the same thing.

These three aspects of organizing our self and selves are each critical. Without a destination in mind, pulling us along, we don’t go anywhere. The power of knowing that we want to be somewhere other than ‘here’ is essential.

Movement toward that destination is a learning journey that includes both the process by which I see the destination as well as the journey I undertake to get to the destination.

With all of this, we live with great uncertainty in the world. We never know what will come, who we will be in response to what comes and who we will become. As a result, we may never get to an exact destination. Or, we may not get there the way we had planned. Uncertainty requires that we learn along the way. It also means that we don’t know the destination precisely either; it reveals itself over time.

Destination emerges as a result of our learning journey. While it might not be the exact destination aimed for, in hindsight we recognize that we travelled in the right direction. The trip was about moving in a direction, not getting to a specific predetermined destination. This does not undermine the value of having a destination in mind, however. It is the critical element that pulls us into the future we desire.

We have a choice before us about how to live with these three aspects of organizing ourselves. Most significantly, we have a choice to make about how we nurture each of these elements as individuals and collectives. We can create habitats for them to work well with each other. We can create habitats for them to work well with us, organizing ourselves for unknown possibilities of our choosing.

I can create a nest for me.

We can create a nest for us.

When we work with passion, we feed ourselves joy. We also feed the city joy.

It is up to all of us, whether we work as citizens, civic managers, civil society or city builders and developers, to make the city full of what we want: joy. Each of us, in our own ways, when we chase what we are passionate about make remarkable contributions to our places where we live together. When we are full of freedom, growth and joy, so too are our cities.

When we align ourselves with our work, great cities that serve us well will emerge, because our work is aligned with our true selves. What we give our cities is what we receive in return. We create our cities, which create us. Indifference for indifference. Disdain for disdain. Compassion for compassion.

Freedom, growth and joy for freedom, growth and joy.

Beauty, truth and goodness for beauty truth and goodness.

Full of unknown possibility

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

Change comes about when it is ready. Not when I am ready, you are ready, or we are ready. When change is ready.

Back in June I noted Beck and Cowan’s six conditions for change: openness to the potential for change, the presence of solutions for the current problems, sufficient dissonance and turbulence with the present, the ability to overcome the barriers within self and others, insight into the patterns in play, and consolidation of understanding that leads to change.

These six conditions are not a recipe; just ‘doing’ these things is not enough to see change, let alone make change happen or last. Beck and Cowan are very clear on this: even if all conditions are met, awakening new ways of thinking MAY happen. It is not a given.

Change is a complex matter. A small action (or realization) may have huge unintended consequences. It is possible that all conditions could be met and no change would take place. There might not be sufficient dissonance, for example. The potential intelligence might not be there. There could be barriers that can not be overcome. It is possible that we are not even able to see and feel what is wrong with the current life conditions, let alone begin to imagine what new possibilities could exist.

When I look at our cities and how we live together, I see that collectively we are experiencing dissonance with how we live. Everyone seems to be unhappy, some of whom see new ways of being and living together. There seems to be a gap between what we ought to do and what we do that we barely understand as individuals or as a collective.

Changes needed to resolve tension in our cities will come when the conditions are right.

An essential practice: notice if it is time for change. If not, be patient. If yes, seek out the ways you can influence the conditions for change. My next posts will explore other critical practices that support our uneasy journey.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

Is everyone unhappy with how we organize our cities? Citizens don’t like what city hall does. Developers and builders don’t like what city hall does. Civic advocacy groups don’t like what city hall does. I recently worked with a group of city employees who have been battered and bruised by colleagues in city hall, politicians, civil society, developers and builders, and citizens. City hall isn’t happy either; every effort they make doesn’t seem to be right and they can’t see a way through to get it right. They are miserable. Everyone sounds miserable.

I am hungry for something other than fighting city hall.

I am hungry for civic practices that allow us to see what is working, so we can have more of what works.

I am hungry for civic practices that allow us to see what does not working and grapple with solutions in ways that leave everyone’s dignity in tact.

I am hungry for civil society that serves cities.

I am hungry for civic managers that serve cities.

I am hungry for civic builders and developers that serve cities

I am hungry for citizens that serve cities.

_____ _____

This is my quest: to see what it takes for a city to serve everyone and everything in and around cities well.

_____ _____

All aspects of a city need to be healthy for the city to be healthy. We need to be healthy for our cities to be healthy. If our cities don’t serve us well, it is up to us to make it better. Each of us. While some of us have more influence over others to make cities that work for us, no one has enough influence to make what they want happen. Uncertainty is embedded in our cities. How we react to the uncertainty is key; we can fight or we can choose to figure out how to figure it out.

The route we choose creates the conditions for more of what we put our attention: we can have more fighting, or we can figure it out.

City hall isn’t healthy when they constantly hear what’s wrong. Developers and builders don’t build great cities when we don’t ask them to. Civil society doesn’t succeed in keeping us honest to our ideals when we are not open to hearing them. Citizens – at any scale – are not their best when defensively in trenches, sabotaging their best potential.

My fight is of a strange nature. I do not ‘fight’ in a physical way, of course, but also not in mental or emotional ways. I am a warrior of a different kind.

I create the conditions where the various perspectives of the city come out to play, integrating themselves, with give and take, for the purpose of creating a nourishing habitat for the beings that live in and around cities. This will evoke a different sort of warrior in our cities: one who has the calm poise needed to welcome the feedback our world is giving us, who listens to it, who takes wise action. Where cities become warriors for well-being themselves.

No matter how hard and smart we work, we can not shake the unknown. It is always with us. How we respond to the unknown, though, has an impact on how we show up in our communities. Ben Okri plays with the contrast of choices in our response: we can be calm or frantic:

Notice (y)our response to the unknown

We only know two kinds of response

To the unknown

Awe, or noise;

Silence, or terror;

Humility, or paralysis;

Prayer, or panic;

Stillness, or speech;

Watchfulness, or myth-making;

Seeing clearly, or inventing what we see;

Standing, or felling;

Reasoning, or falling apart;

Courage, or cowardice.

From Ben Okri’s “Mental Fight”

The choice to be calm or frantic resides within each of us individually. Our response affects others and at the same time it is always a choice that resides in me when folks are frantic around me. I always have a choice. Each of us always has a choice. And this choice quite dramatically affects how I show up in my life, my work and my community. I can cause a stir that distracts from what’s happening in the world, or I can cause calm that sees the stir for what it is: an opportunity, rather than a fight.

Noticing my, and our, response to the unknown is crucial for our uneasy journey as individuals, collectives, and as a species, in cities. When conscious of what is going on in our internal worlds, we are better able to serve ourselves, others and our cities well.

An essential practice: notice (y)our response to the unknown. My next posts will explore other critical practices that support our uneasy journey.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

I started this chapter with a reminder that cities are meant to feel uneasy. And living in cities, and the process of creating and recreating them, is a journey in two senses: as we travel along in our evolution and as an act of learning.

The learning that takes place in our cities is a result of our drive to endlessly think, make and do new things to improve the quality of our lives. The work we do creates our cities. But getting improvement means we need to scratch the itch, for the itch is what tells us that there is something to improve. It bothers us, compelling us to do something about it.

We are itching for improvement. At any scale (self, family, neighbourhood, organization, city, region, nation, planet), we experience akrasia, the gulf between what we know we ought to do and what we actually do. This tension serves as the evolutionary driver of cities and our own development.

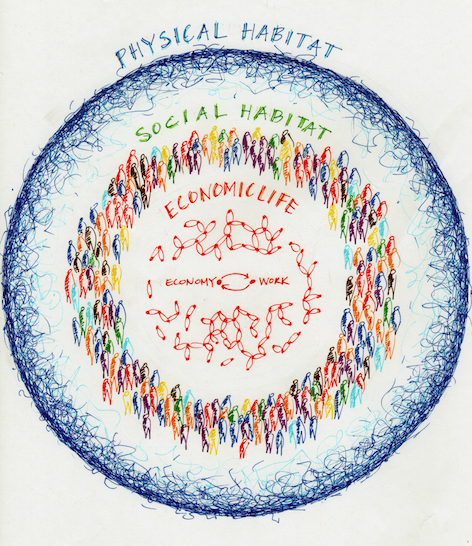

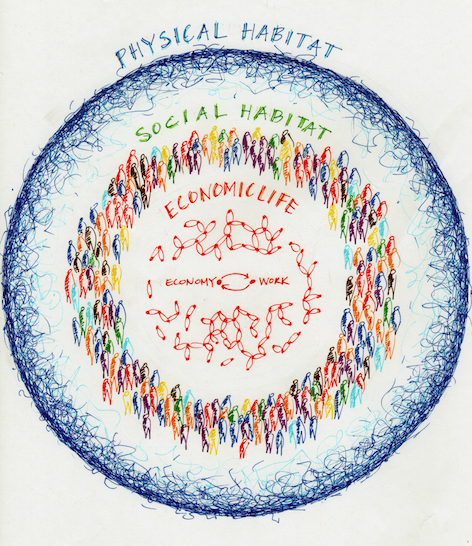

Our response to our habitat (our surroundings) is what drives the creation of new work, and the development of new work is a survival skill. But this only takes place if and when we are receptive to receiving feedback from our surroundings. Our ability to seek feedback and receive it is a survival skill – at any scale. This practice is critical for our cities, for they are habitats we create for express purpose of improving life. We shape our cities and they, in turn, shape us.

Our ability to evolve our cities is a survival skill. Understanding that our cities, and all their inhabitants, are on a journey together is crucial. We do not know exactly where we are going and we never will. What we do know is that we are going on this trip together. Ensuring a healthy connection between our work and our habitat is crucial, and this connection is dependent upon the social habitat we create for ourselves, for it is our social habitat that invites and allows feedback to flow. If our social habitat is not well, our actions are ill-informed and possibly harmful. If healthy, we are wise. For our cities to be well, we need to create a social habitat where feedback flows.

It is time to embark explicitly on a journey together where we create a social habitat that brings the best out of us, that support each of us, and the collective, in the discomfort we find when we start to scratch the things that itch. We need to organize ourselves to physically build cities that work for us, AND we need to organize ourselves to support each other in the uneasiness of city building.

This is tough work, and critical work. And it will never end because we are forever recreating our world in city, creating new life conditions to which we adapt, creating new life conditions to which we adapt, creating new life conditions to which we adapt etc.

Tomorrow, on Wednesday October 24, 2012, I am spending the day with 18ish to 30ish year-olds in Edmonton to declare the impossibly awesome neighbourhood possible. For this event, I am working with The Natural Step Canada to create a social habitat in which dreams come true. I’ll let you know how it goes.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap football shirts |

cheap-football-shirts-prodirectsoccer |

cheap-football-shirts-discountfootballkits |

cheap-football-shirts-subsidesports |

cheap-football-shirts-uksoccershop |

cheap-football-shirts-mandmdirect |

cheap-football-shirts-mandmdirect-spot |

cheap-football-shirts-sportsdirect |

cheap-football-shirts-startfootball |

cheap-football-shirts-manutd |

cheap-football-shirts-directsoccer |

cheap-football-shirts-celticsuperstore |

cheap-football-shirts-classicfootballshirts |

cheap-football-shirts-prosocceruk |

cheap-football-shirts-kitking |

cheap-football-shirts-historicalkits |

cheap-football-shirts-teamsportdirect |

cheap-football-shirts-soccerkits |

windows 7 product key |

windows 7 key |

windows 7 product key |

Windows 7 Key ,

Windows 7 Key ,

Windows 8 Key ,

Windows 10 Key ,

Office 2013 Key ,

Office 2010 Key ,

Office 2016 Key ,

70-981 ,

700-501 ,

400-051 ,

200-310 ,

70-480 ,

642-999 ,

400-101 ,

ADM-201 ,

70-534 ,

400-101 ,

400-201 ,

599-01 ,

640-692 ,

640-875 ,

640-911 ,

642-997 ,

642-999 ,

700-037 ,

LX0-103 ,

70-347 ,

PR000041 ,

EX200 ,

640-692 ,

ITILFND ,

1z0-808 ,

300-208 ,

M70-201 ,

642-999 ,

icbb ,

n10-006 ,

pegacpba71v1 ,

70-533 ,

642-996 ,

102-400 ,

mb2-708 ,

070-483 ,

350-080 ,

A00-211 ,

1Z0-061 ,

70-486 ,

1z0-808 ,

ADM-201 ,

A00-211 ,

3002 ,

CBAP ,

1Z0-061 ,

640-911 ,

70-487 ,

3002 ,

MB5-705 ,

352-001 ,

70-346 ,

210-065 ,

M70-201 ,

070-483 ,

100-101 ,

642-035 ,

NS0-157 ,

EX300 ,

350-018 ,

A00-211 ,

PMP ,

642-996 ,

70-461 ,

IIA-CIA-PART1 ,

210-065 ,

300-101 ,

640-911 ,

OG0-093 ,

642-732 ,

642-035 ,

LX0-103 ,

pegacpba71v1 ,

500-260 ,

640-875 ,

mb2-708 ,

ex300 ,

c_tscm62_66 ,

1z0-060 ,

ns0-157 ,

2v0-621 ,

70-412 ,

400-201 ,

itilfnd ,

mb2-704 ,

1z0-804 ,

lx0-103 ,

210-060 ,

070-486 ,

a00-211 ,

cbap ,

300-320 ,

200-310 ,

642-999 ,

210-060 ,

101 ,

70-980 ,

300-208 ,

70-480 ,

hp0-s42 ,

1z0-804 ,

cca-500 ,

C2180-410 |

640-554 |

101 |

1V0-605 |

CCD-410 |

1Z0-061 |

HP0-S42 |

70-461 |

70-414 |

1Z0-062 |

74-678 |

CCD-410 |

1z0-432 |

C2070-991 |

200-120 |

74-697 |

300-101 |

70-534 |

70-243 |

M70-301 |

70-331 |

C2210-422 |

CCA-500 |

100-101 |

640-554 |

3002 |

1Z0-061 |

98-367 |

300-101 |

IIA-CIA-PART1 |

LX0-104 |

LX0-103 |

ITILFND |

352-001 |

MB2-708 |

PMP |

350-018 |

70-411 |

70-533 |

300-135 |

IIA-CIA-PART1 |

642-732 |

642-998 |

1Z0-804 |

C_TSCM62_66 |

101 |

PR000041 |

642-999 |

LX0-104 |

ICBB |

300-135 |

ITILFND |

200-310 |

640-875 |

SY0-401 |

1Z0-803 exam |

220-801 exam |

300-101 exam |

70-467 exam |

CISSP exam |

SY0-401 exam |