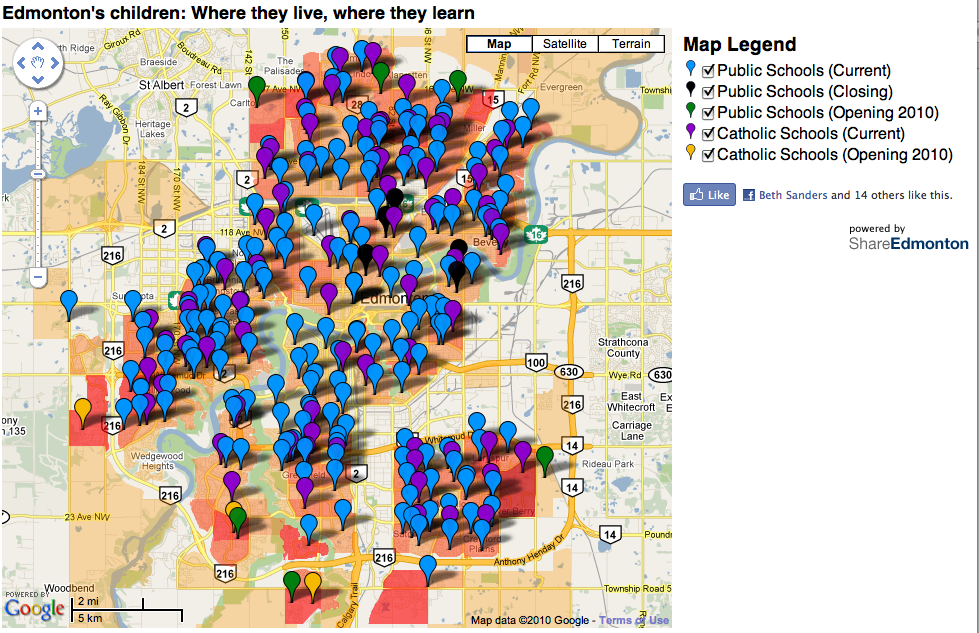

The Edmonton Journal’s Sarah O’Donnell and Edmonton programmer Mack Male, have painted a picture for Edmonton residents and decision makers about how our city is growing, especially in light of recent Edmonton Public Schools decisions to close inner city schools.

The Edmonton Journal’s Sarah O’Donnell and Edmonton programmer Mack Male, have painted a picture for Edmonton residents and decision makers about how our city is growing, especially in light of recent Edmonton Public Schools decisions to close inner city schools.

The article and mapping show us where young families are living, and by implication where schools are needed based on the numbers of children nearby. Using this logic, it makes perfect sense to close schools where there are fewer children. Need is based on numbers of children, no more no less. Families move to the suburbs and school trustees follow the families. It’s that simple.

Or is it? This conversation seems to make several assumptions. I offer several below to test if they are the assumptions we are using, and /or if we wish to consciously create a new set of assumptions. They drive how we build and adjust the city we live in, the city we are designing while living in it.

Assumption 1: Growth just happens. Growth happens where we choose to make it happen. Cities choose where growth will happen and has a legislative framework to guide growth. Ultimately, the decision makers are City Council. There are, however, many other decision makers that influence how and where we build: home buyers, developers and builders, school boards, health providers, realtors, etc. We spend a lot of time and energy designing and building infrastructure to accommodate us living in this place together, and it is not haphazard. It takes years (and decades) to plan for Anthony Henday, LRT routes, water and wastewater systems, electricity, gas and our extensive roadway system. We build all of this in the public eye. None of it “just happens.”

Assumption 2: We have unlimited funds for infrastructure now and in the future. We expand our city without contemplating the full costs of doing so. We let school buildings close. We let vacant land remain vacant when servicing infrastructure is near by. We let land, and all the utilities serving that land, remain underutilized. If we are not able to maintain our current infrastructure well now, how do we expect to do so in the future? City Hall, for example, faces huge capital and operating budget challenges, yet we continue to spread ourselves thin. We behave as if we have unlimited revenue now and in the future. Are our pockets (as taxpayers) that full?

Assumption 3: We need a lot of space from our neighbours. It seems that having oodles of space – in our yards and homes – drives Edmonton’s design. Why are we afraid of being close to other people? Or sharing park space instead of large private yards? What is behind this? What makes neighbours bad, especially if there are a lot of them? Perhaps the devil is not in the density, but in the design of how we build the buildings and the space around them. What if we built exciting spaces and ensured the services were on hand – like schools, LRT – to create viable neighbourhoods. Viable from a social, environmental and fiscal perspective. We have yet to really pay for all this space we are enjoying.

Assumption 4: School boards don’t build cities – City Hall does. Schools have an absolutely critical role to play in physically building cities – look at the schools and green spaces everywhere. They also play a key role in supporting the well-being of neighbourhoods. Schools are critical formal and informal gathering places that help make a neighbourhood healthy. A school board’s decisions are critical. They are not isolated from everyone else’s actions. Our city builders include school systems (secondary and postsecondary), health systems, energy and water systems, city hall, and our builders and developers. No one entity or initiative works completely in isolation – they all have a piece of the neighbourhood puzzle.

What if we switched those assumptions for the following principles in decision making at many scales (from citizen up to a large city network of organizations):

- Use current infrastructure before building new

- Create and design for exciting spaces where people want to spend time

- Bring nature to the people and people to nature

- Create and support a transportation system that moves people and goods efficiently (rather than the most cars/trucks efficiently)

- Integrate the interests and dreams of citizens, community organizations, our city institutions and our city builders

- Consider the cumulative costs of our city design choices – actively seek feedback on our choices

I suspect that these principles seem innocuous, but they are not when we have the feedback systems in place to truly understand if our actions are in line with our goals. The City of Edmonton, in creating and providing open source data, is providing a critical feedback loop for Edmontonians to understand how the city we are creating works. There are exciting conversations ahead in Edmonton’s future.

Our collective actions -as citizens, community organizations, school systems, business owners, city government, health providers, developers, builders, realtors, home buyers, etc. – create our city. Is it the one we want?

I wonder if the evidence shows that we are getting what we want, or if we are getting what “just happens.”

http://www.edmontonjournal.com/news/edmonton/schools+meet+suburbs+needs/3067140/story.html ttp://www.edmontonjournal.com/news/school+map/3056784/story.html