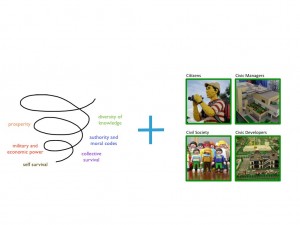

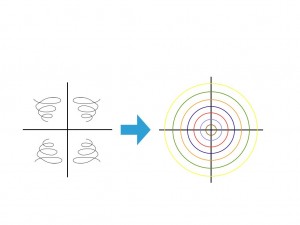

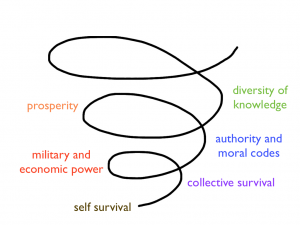

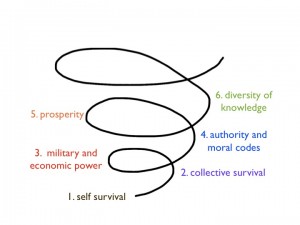

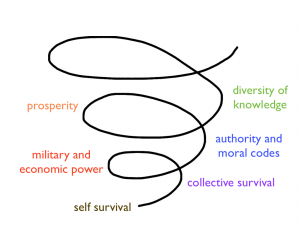

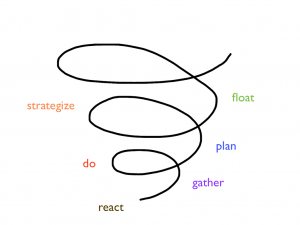

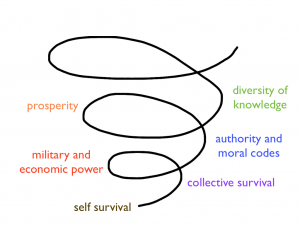

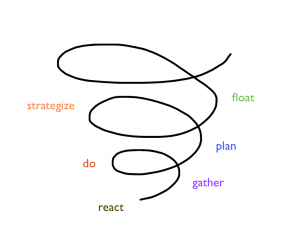

The activity of planning cities is a kind of work that has emerged with cities. It is a mode of organizing that began in Canada with land surveyors and engineers. The work of planners and planning in Canada is recent; Canada’s Commission of Conservation hired Britain’s Thomas Adams in 1914 as its Town Planning Advisor. His work supported the creation of town planning legislation across Canada, and a whole new area of work distinct from that of surveying and engineering. For Adams, the additional focus of planning was to improve civic conditions[1]. This was the beginning of a structure (legislation) and a profession dedicated to contributing order to settlements across Canada, work that emerged with the fourth purpose of the city (Figure 1), and the fourth level of organizing (Figure 2). (For more on the evolution of city purposes and modes of organizing, please see Is the unplanned city unplanned? Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4).

The activity of planning our communities – even just thinking about planning – has played a critical role in the shape our communities today. Gerald Hodge and David L. A. Gordon, authors of Canada’s primary text for students of planning Canadian communities, note:

…the regard for planning and making plans is strong. Even in… contentious situations, the essential debate is not about the need for planning, but for better planning – not whether but how it should be done.”[2]Citizens, developers and builders, civil society and our various public institutions and politicians are always ready to tell planners about needed improvements. And they are right – there are many improvements to be made. What we ought to be wary of is the assumption that it is up to planners to make the changes.

Today’s challenge – recalibrating the purpose of planning, plans and planners

This is the challenge that faces planners, citizens and decision-makers today: our communities function with an extended focus, broadened purpose and less concentrated decision-making processes. The formal act of ‘planning’ as we recognize it today, with zoning by-laws and area structure plans, is in response to life conditions of a certain time, geography, challenges, and social circumstances. It is as set of activities that fits the era in which Thomas Adams worked. In today’s world the work of organizing a city belongs to many. The planning profession is simply one of many kinds of work. The work of organizing ourselves to thrive belongs to all of us. In 1922, Thomas Adams stated: “Cities do not grow – all of them are planned.”[3] It is as though we build them as we build a building, with a complete set of plans. That just doesn’t happen with cities. They do grow.

None of this means that plans and planning are not relevant. Plans do have a purpose. Having a plan means that we know where we are going and what it will take to get there. A plan documents our shared purpose, intention and intended actions to reach our goals. In every aspect of life, this is a critical function. Specific to city planning, Hodge and Gordon describe it this way: a plan is “for the purpose of achieving a goal desired by its citizens… community planning is about attaining a preferred future built and natural environment.”[4] They cite two reasons why a community makes plans: to solve some problems associated with its development; and/or to achieve some preferred form of development.[5] This is work that makes a meaningful contribution to cities.

In conventional planning circles, the professional planners are charged with this work. Citizens, civil society, civic builders and developers along with politicians provide feedback to planners through formal public engagement activities. Yet we are growing into an understanding that city hall is not the only player who organizes a city, but that there are many others involved. Numerous organizations, activities and events shape the city without city hall’s direction. Environmental groups have had an influence on our tolerance for weeds. Arts foundations find the funds to build new museums and art galleries. Business leaders join forces to advance technology research and innovation. The university hospital chooses to emphasize health research and expands its facilities. School boards decide to allow families to choose their schools. Citizens choose where to live in relation to employment/schools/services. All and each of these players shape our complex cities.

Citizens, civil society, civic builders and developers are increasingly demanding a role in the process of planning our communities. Even departments inside city hall are hungry for ways to integrate their work with planners. As a result, the role of the plan has evolved into something new. City plans are no longer simply the blueprint early land surveyors and engineers prepared for orderly development. A new kind of work is being called for that supports an expanded view of what it takes to make cities that are healthy habitats for citizens.

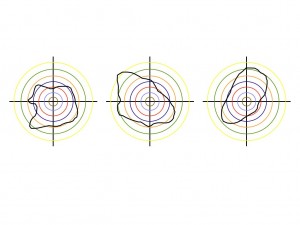

The value of plans is in their intention and common direction. They are now more about shape and spirit, rather than control. There are times when control is important, but the scope of planning is widening and more and more aspects of planning are about much more than control. As an activity, planning has to hold a destination in mind, allow for learning and adjustment along the way, and recognize that we do not know exactly what we are going to end up with and we can’t control that. Part Two and Part Three of this writing endeavour will flesh out how to organize ourselves with kind of understanding. For the moment I offer this:

The next post will conclude Chapter 2 – The Planning Impulse with a question: Is planning even the right word any more? Chapter 3 – The Thriving Impulse, will be a theory side trip into what it means to thrive before thoroughly exploring the City Nestworking model above for the remainder of the book in Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence and Part 3 – Nest City.

[2] Gerald Hodge and David L.A. Gordon, Planning Canadian Communities, p. 3

[3] As quoted by Hodge and Gordon

[4] Gerald Hodge and David L.A. Gordon, Planning Canadian Communities, p. 5

[5] Gerald Hodge and David L.A. Gordon, Planning Canadian Communities, p. 5

Other Sources –

Beck, Don Edward and Cowan, Christopher C., Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford (2006), particularly pages 52-56.

Hamilton, Marilyn, Integral City: Evolutionary Intelligences for the Human Hive, New Society Publishers Inc., Gabriola Island (2008)

Sanders, Beth, “From the High Water Mark to the Back of the Fish Flakes: The Evolutionary Purpose of Cities,” Vol 51, No. 4, p 26-31, Plan Canada. Print publication of the Canadian Institute of Planners.