Integral intelligence is about charting patterns. Since I began blogging Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities on May 1, 2012 (click here for the first blog), I have used three of the four integral maps introduced by Marilyn Hamilton in her body of work called Integral City (here are links to her book and website).

The four integral maps to look at cities in a whole, integrated fashion are:

- The nested holarchy of city systems

- Spiral Dynamics – the complex adaptive structures of city change

- The integral map

- The scalar, fractal relationship of micro, meso, macro human systems

1. Nested Hierarchy of City Systems

I first introduced the nested holarchy of city systems when describing the role of work and our work life as the evolutionary spark that began our migration across the planet, then into cities, and the subsequent growth of our cities. We are driven to do more than merely survive, so we constantly find ways to think, make and do new things. The result is that we change our habitat along the way – we create settlements and cities (and many other things that physically change our habitat). More importantly, our work, at every scale in the city, creates the conditions for even more ways of thinking, making and doing new things: innovation. Our cities are engines of innovation, which means that the development of cities is a survival skill.

For Hamilton, to look at a city as whole we must contemplate the city as a human system, which is comprised of a nest of systems, each of which are themselves whole. Each of which has its own level of complexity that includes the preceding “smaller” systems.

The value of this map is that at minimum, it reminds us to thing of city life at more than one scale. It also reminds us that to work at any scale, we must also work with the systems that make up that system. If working at the neighbourhood scale (5), then we must also work at the individual, family/clan, group, organizational scales as well.

Hamilton has made a recent blog post on this if you are interested. Other Nest City posts that include this map are: Cities: the result of our evolving interaction with our habitat, Work at scale to serve the city, and The city as a nest.

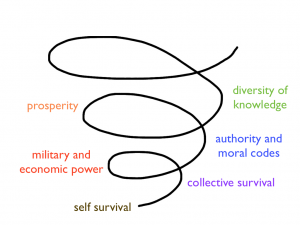

2. Spiral Dynamics – integral

The Nest City blog next introduced Spiral Dynamics as a means to map the evolution of the purpose of cities. A series of posts (Is an unplanned city part 1, part 2, part 3 and part 4) tell the story of St. John’s, Newfoundland and reveal how as the levels of complexity change (as the scales of system in the nested holarchy of city systems get larger), we adapt to provide structures that support new levels of complexity. As the purpose of a human settlement evolves, we shift and adjust our values and priorities to organize ourselves in response to changing conditions. These posts are a window into how the Spiral shows up in the city.

Three additional posts outline how the Spiral works: A primer on the emerging spiral, 7 principles frame the emerging spiral, and Conditions for evolutionary expansion.

The value of this map is not just in the map itself. The places on the map tell us about the values of that spot, and the things that motivate people and systems from that spot. This understanding has huge implications for designing and communication with city systems.

The additional value of this frame is the understanding that movement up or down the spiral is always in response to life conditions – our habitat. This is so critical for cities – for our cities are our habitat, made by us.

Both of these maps are intensely connected to our drive to thrive in cities. The nested holarchy reminds us that cities are a systems made of systems and part of larger, expanding systems. Moreover, as we build our cities we are creating the conditions for our own movement up the Spiral. We are creating the conditions for our own evolution.

The next post will address the two remaining maps of integral intelligence: the integral map, and scalar, fractal relationships.