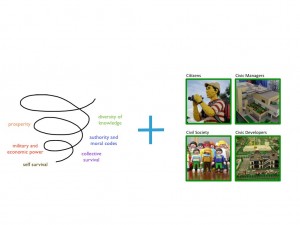

A city is made up of multiple perspectives, purposes and modes of organizing. In Is an unplanned city unplanned? Part 3 and Part 4, I showed the purposes for cities that emerge and the ways we organize in accordance with each purpose. In City – a dance of voices and values, I made the connection between purpose/organizing and Hamilton’ four voices of city life: citizens, city managers, city builders and civil society (Figure 1).

A city is made up of multiple perspectives, purposes and modes of organizing. In Is an unplanned city unplanned? Part 3 and Part 4, I showed the purposes for cities that emerge and the ways we organize in accordance with each purpose. In City – a dance of voices and values, I made the connection between purpose/organizing and Hamilton’ four voices of city life: citizens, city managers, city builders and civil society (Figure 1).

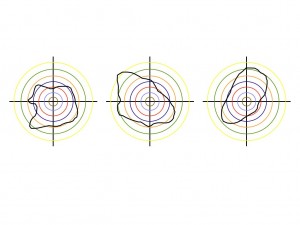

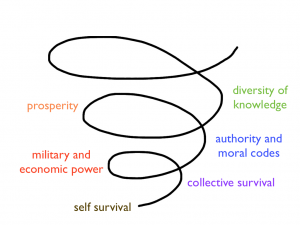

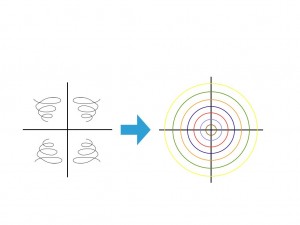

Three cities, or three different points in time in the same city, could have completely different ‘maps’ of where their values lay. Imagine dropping the spiral of city purposes on the four quadrants of city voices (Figure 2). Instead of spirals, imagine concentric circles, radiating out from the center, illustrating the emergence of city purposes and modes of organizing. The values in play can be seen and mapped for all four voices of the city.

Three cities, or three different points in time in the same city, could have completely different ‘maps’ of where their values lay. Imagine dropping the spiral of city purposes on the four quadrants of city voices (Figure 2). Instead of spirals, imagine concentric circles, radiating out from the center, illustrating the emergence of city purposes and modes of organizing. The values in play can be seen and mapped for all four voices of the city.

Here are three examples (Figure 3):

On the left, most city builders value competition and prosperity while a good portion of citizens and city managers have a focus on authority and rules. A portion of civil society puts emphasis on equality. In the center illustration, the City Managers are in “turf mode”, with little power in authority. In contrast, citizens, civil society and city builders appear to be in a position to take advantage of a lack of authority. In the city on the right we see citizens valuing authority and moral codes while civil society and city managers are seeking much less formal structure with value systems that flatten hierarchy. The city builders appear to be in turf-oriented competition. Each map presents a different picture of what is valued in that city, from the perspective of those voices.

Varied purposes of cities, along with their associated levels of organizing that correspond with those purposes, coexist. This means that many modes of organizing are occuring simultaneously. As we organize ourselves in cities, there are people attending to our various collective needs: individual organizations might be in survival mode due to budget cuts; new immigrants assemble to cultivate a sense of belonging and identity in a new place; the fire department responds to emergencies in ‘do’ mode; municipal governments establish order with by-laws regulating on-street parking; the Chamber of Commerce seeks strategic economic advantage; social justice groups demand participative decision-making processes. As a whole, these are activities we undertake to organize ourselves and create habitats in which we will thrive. One of the ways we organize is to plan, where we document where we intend to go and how we think we’ll get there.

When our basic survival needs are met, we organize ourselves with the aim to thrive. As our cities began to grow, there was a point where we saw a need for order. Eventually, we saw a need to create a new profession: city planning. We saw a need to articulate, and document, a desired goal to improve our cities (no one plans for things to be worse) and the details of how to get there. We aim in the direction of making things better, and we identify the steps we need to take to make things better. This is planning in its simplest form. It is work we are all engaged in, as profession planners and as citizens.

Planning our cities is work that belongs to all of us at once. The Integral City model reminds us that we all have a role to play in city life. The city builders organize themselves to physically construct our city and they make plans to do so. Civil society organizes the social and cultural life in our cities; they look after various non-physical qualities of our cities. Citizens, in our day-to-day life bring life to the city with every choice we make, particularly when we follow our passions in our work – whether paid or unpaid. City managers have a role to play to create the minimal critical structure on which cities sit: our municipal government, health services, education, etc. Each of the city’s voices shape the city, all at once, creating a world of messiness and uncertainty because no one entity has control of a city. This understanding is critical for citizens and professional planners alike.

Planners used to be (and some still are, as appropriate) the people that write the plans for political approval. As policy writers, they take direction from city council or propose policy to city council. They ask the public and stakeholders what they think and make recommendations to Council. The policy may be a transportation plan, a facility plan for a school division, a plan for future subdivisions. We, as the public, assign great responsibility to this profession. We also miss-assign this responsibility because professional planners shape and influence our cities, but it is a co-creative process. Professional planners are expected to have the answers – and the recipe – but that is not how planning happens. Planners do not have a recipe, let alone all the ingredients.

In my next post I will explore this question: What is the purpose of plans and planning in today’s context?

Sources –

Beck, Don Edward and Cowan, Christopher C., Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership, and Change, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford (2006), particularly pages 52-56.

Hamilton, Marilyn, Integral City: Evolutionary Intelligences for the Human Hive, New Society Publishers Inc., Gabriola Island (2008)

Sanders, Beth, “From the High Water Mark to the Back of the Fish Flakes: The Evolutionary Purpose of Cities,” Vol 51, No. 4, p 26-31, Plan Canada. Print publication of the Canadian Institute of Planners.

Wilber, Ken, A Brief History of Everything, Shambhala Publications Inc., Boston (1996, 2000)