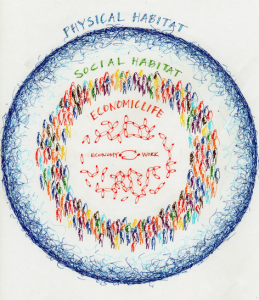

A city that meets our needs pays attention to three critical relationships within the city’s habitats:

- between economic life and social habitat;

- between social habitat and physical habitat; and

- between economic life, through social habitat to physical habitat.

In the first relationship, between our economic life and our social habitat, we make personal investments to come up with ideas and turn them into new work. Likewise, how we organize ourselves shapes our collective investment in the idea – the labour we put to it, the skills we put to it, or simply the ‘human potentialities’, as Jane Jacobs put it, shape what becomes of the idea. In the workplace or in a community, for example, new ways of thinking, making and doing new things emerge when welcome; they likely remain invisible or nonexistent if the social habitat is hostile.

At a societal level, sometimes we just are not ready yet for new things until conditions change. Sixty years ago my home was built with no insulation. Energy prices were low and the notion of human-caused climate change did not exist. In contrast, today we have building codes with minimal requirements for energy efficiency and government grants to upgrade older homes. As our social habitat changes, so does our work. And as our work changes, so does our social habitat. Notice the adjustments we have made to life with computers, the internet, social media, etc.

This relationship between our social habitat and our economic life is critical to Jacobs’ refueling principle: “… no matter how efficient a cow may be, if it doesn’t self-refuel, it’s a dead cow. Self-refueling is so fundamental to survival, and to all other process of life made possible by survival, that conceptions of whether it is a good or bad thing are pointless.”[1] The ideas that survive in cities (new work) must be applied or used for economic life to thrive. This is the essence of refueling – capture the good ideas, let new ideas emerge from them, try them out, see if more new ideas emerge. The more this takes place, the stronger and healthier our economic life. In our social habitat, we must create the appropriate ‘equipment’ to capture and make use of the ideas, as well as finding additional ways to capture ideas. The social habitat supports, hinders, or removes our ability to self-refuel. This is where we demonstrate our tolerance for diversity, new work and change.

The second relationship in the city habitat is between the social habitat and the physical habitat. This is where we notice our physical conditions and whether they are changing or not. This relationship is about our receptivity to our physical reality, when we notice how habitat creates us and how we create habitat. An open relationship between our social and physical habitats is exemplified by our ability to take in the good and bad news.

The third relationship in the city habitat, between economic life and physical habitat involves travelling through the social habitat. Our social habitat creates the conditions for a relationship with our physical habitat and our economic life and between our physical habitat and our economic life. In this relationship we recognize explicitly that the city affects our work and that our work affects our city. We boldly look for feedback to link the three spheres.

Each of these relationships involves our social habitat, where there are degrees of mutual support and information exchange. On a continuum, we are either open to the exchanges between habitats, or closed. Like a tap, the choice is open with maximum flow, or closed with no flow. In the middle the tap is open partway, with flow constricted. And the degree of relationship compounds: the first two relationships must be open in order for the third relationship to take place. If one is open only partially, the third relationship will also be partial; it is only as open as its constituent relationships.

As a whole, the city is a habitat that encompasses our economic, social and physical habitats. Our social habitat allows the new work that creates and recreates our cities to take place in the context of our physical habitat. This means that new work is needed to create a social sphere that allows the necessary data to go back and forth between our physical environment and our economic life. The quality of the relationship between our economic life and our social and physical habitats dictates our ability to generate cities that meet our economic, social and physical needs.

This framing reorganizes how we think of balancing the well-being of economic, social and physical factors for sustainable development. My next post will explore the value of reorganizing these elements.