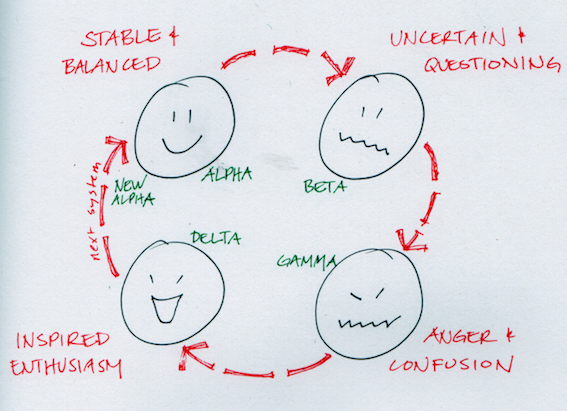

I started this chapter with a reminder that cities are meant to feel uneasy. And living in cities, and the process of creating and recreating them, is a journey in two senses: as we travel along in our evolution and as an act of learning.

The learning that takes place in our cities is a result of our drive to endlessly think, make and do new things to improve the quality of our lives. The work we do creates our cities. But getting improvement means we need to scratch the itch, for the itch is what tells us that there is something to improve. It bothers us, compelling us to do something about it.

We are itching for improvement. At any scale (self, family, neighbourhood, organization, city, region, nation, planet), we experience akrasia, the gulf between what we know we ought to do and what we actually do. This tension serves as the evolutionary driver of cities and our own development.

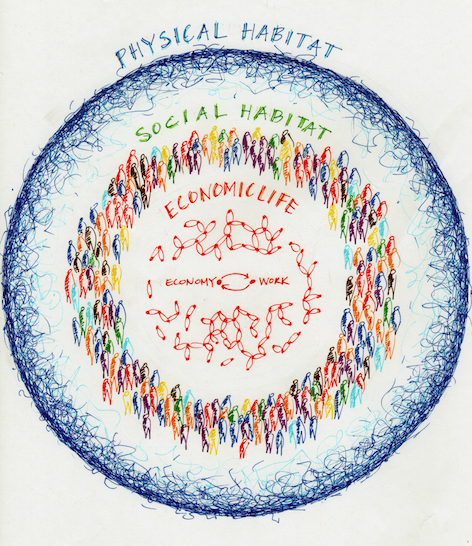

Our response to our habitat (our surroundings) is what drives the creation of new work, and the development of new work is a survival skill. But this only takes place if and when we are receptive to receiving feedback from our surroundings. Our ability to seek feedback and receive it is a survival skill – at any scale. This practice is critical for our cities, for they are habitats we create for express purpose of improving life. We shape our cities and they, in turn, shape us.

Our ability to evolve our cities is a survival skill. Understanding that our cities, and all their inhabitants, are on a journey together is crucial. We do not know exactly where we are going and we never will. What we do know is that we are going on this trip together. Ensuring a healthy connection between our work and our habitat is crucial, and this connection is dependent upon the social habitat we create for ourselves, for it is our social habitat that invites and allows feedback to flow. If our social habitat is not well, our actions are ill-informed and possibly harmful. If healthy, we are wise. For our cities to be well, we need to create a social habitat where feedback flows.

It is time to embark explicitly on a journey together where we create a social habitat that brings the best out of us, that support each of us, and the collective, in the discomfort we find when we start to scratch the things that itch. We need to organize ourselves to physically build cities that work for us, AND we need to organize ourselves to support each other in the uneasiness of city building.

This is tough work, and critical work. And it will never end because we are forever recreating our world in city, creating new life conditions to which we adapt, creating new life conditions to which we adapt, creating new life conditions to which we adapt etc.

Tomorrow, on Wednesday October 24, 2012, I am spending the day with 18ish to 30ish year-olds in Edmonton to declare the impossibly awesome neighbourhood possible. For this event, I am working with The Natural Step Canada to create a social habitat in which dreams come true. I’ll let you know how it goes.

_____ _____ _____

This post forms part of Chapter 4 – An Uneasy Journey, of Nest City: The Human Drive to Thrive in Cities.

Nest City is organized into three parts, each with a collection of chapters. Click here for an overview of the three parts of Nest City. Click here for an overview of Part 2 – Organizing for Emergence, chapters 4-7.