The human journey thus far appears to have been sparked by new ideas. In yesterday’s post, it distilled down to thinking, making and doing new things. The spark of new ideas continues.

Physicist Geoffrey West has found that as a city grows, it becomes more innovative. A city 10 times the size of a neighbouring city is 17 times more innovative. A metropolis 50 times bigger than a town is 130 times more innovative. For Steven Johnson, the city is an engine of innovation because it is an environment that is powerfully suited for the creation, diffusion and adoption of good ideas. His conclusion about West’s work: in one crucial way, “human-built cities broke from the patterns of biological life: as cities get bigger, they generate ideas at a faster clip… despite all the noise and crowding and distraction, the average resident of a metropolis… [is]… more creative.” (Readers interested in a quick synopsis of Johnson’s thinking on the conditions that create innovation will enjoy this 4 minute you tube video. A strong connection is made between innovation and cities specifically can be found in his book, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software.)

As a species, we have an impulse to innovate, to seek new ideas and new ways of doing things. We strive to improve the quality of our lives. It turns out that cities are engines of innovation and, as noted in my May 1, 2012 post, Are people growing cities or are cities growing people, these engines of innovation are running fast.

Consider that innovation is simply new work – new ways of thinking, making and doing new things as described in yesterday’s post. New work, and the constant generation of new work, is a way for us to adapt to our changing world. If our work always stayed the same, our species would not have travelled and settled across the planet. We would not have created agriculture and cities. New work allows us to evolve. It spurs our migration to, and the growth of, cities. In return, cities create the conditions for more new work. Cities are the habitat we create for ourselves to create the conditions for us to learn and grow, endlessly seeking to improve our lot in life, through our work.

The work we do as individuals, and upwards in scale as a species, is first about our survival. It is what we do, for example, to make money to pay for housing, to feed and clothe our families and to meet our recreational and material interests. But our work, when we generate new ways of thinking, making and doing, offers something larger. Our work offers opportunities for self, family, neighbourhood, city, nation, species, to adapt to the changing world. I imagine these kinds of work in our ancestral tribe of 11,000 in Africa: find food, prepare food, provide and maintain shelter, look after children, look after the physical and spiritual well-being of the people, and provide wisdom and leadership, as necessary. In contrast, the kinds of work in today’s cities continue to evolve. It includes these and many other kinds of work as we continually seek and find new work. Yet all of these iterations of new work in cities come about when our basic needs are met – when we have time to explore, invent and pursue our passions.

Work is hard. It may be drudgery, a grind. It may be a place, but it is more ubiquitous than that: we work at things all day, every day. When something succeeds, or functions well, we say it ‘works’. The truth is, work is a ‘work out’. To get the results we seek we need to be willing to put in effort and ‘work’ at it. When we do, presumably, it will ‘work’ better. We have a desire to ‘work’ things through so they ‘work’ better, perhaps easier. When we search for new work, it becomes a learning impulse, a desire to find new and better ways of doing things that are of interest to each of us. Whether paid or unpaid work – it is simply what we do as we make our way through life.

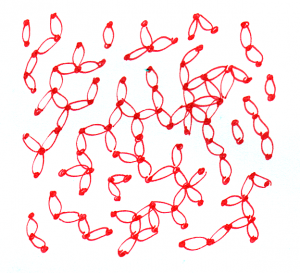

Our work is what we offer the world, whether to make ends meet or because we love to do what we do. We exchange our work with others for goods and services in return for things we need. What we offer and what we receive constantly informs and influences us. Our work offers knowledge and skills to others, who in turn offer us opportunities to do our work. If we choose, we develop our work further, looking for new ways of thinking, making and doing. This relationship is what Jane Jacobs called our economic life (Figure A): the transaction between our work and the world. This relationship is an exchange – a transaction – that is not limited to money, and is much broader. It is, simply, a relationship between me and the world – the economy.

Work for me these days includes chairing a series of meetings for the City of Edmonton as a group of employees and stakeholders write a growth coordination strategy. For this work I am paid. My work life also includes writing, shoveling my neighbour’s sidewalk, taking my turn to get my son and his friends to soccer practice and my share of housework. While I am paid for the work with the City, I am not getting paid for the other work, but I do get something in return: I have a good relationship with my neighbor who keeps an eye on our home when we are away, my son’s teammates families take turns driving to practices, and my whole family contributes to the physical well-being of our home so we are all able to participate in activities we enjoy.

This dance between self and other, and what we offer to each other, is our economic life. Collectively, when we add more and more people into this relationship, I can imagine the relationships in a city: our economic life (Figure B). When we develop and offer new work, we offer something far greater than we imagine: we create the conditions for more people to create new work and follow their passion. We create a habitat for innovation.

The answer to Tuesday’s post is that people are growing cities AND cities are growing people. This is taking place because we create habitats for innovation, cities, which in turn bring new challenges for which we need innovation to resolve. By doing new things we are changing the world around us, necessitating more adaptation and new work.

Cities are engines of innovation and innovation is the engine of cities.

It turns out that growing cities is a survival skill.

New work generates cities and the capacities we need to adapt to our changing world. And the very habitat we build for ourselves – our cities – is where we create that new work.

My next post will explore more specifically the relationship between the development of new work and cities. Another take on Jacobs’ work a few decades later…