We explored how conversational leadership takes place, and how through conversational leadership, the doors open to co-create wise action and change in our organizations and communities.

Last week I relished the opportunity to show up and be hosted, rather than be host at the latest Art of Hosting gathering in the Edmonton area. While I worked hard to get the word out to people I know who are searching continually for ways to be well with others, it was wonderful to arrive without having to organize anything. Rather than attending to the details of the venue, process design considerations etc., I was able to arrive in a different way: most fully and selfishly expecting to learn at every turn. As host, I expect to learn at every turn, but there is a slight but meaningful distinction when being hosted – a bit more freedom to explore and invest in self. It is a marginal distinction with significant implications.

The implication – and gift – for me is remembering how difficult it can be for me to be hosted. Hence, I have been pondering the difference between being host and being hosted.

The smililarities between being host and being hosted are striking: both require welcoming the stretch of learning together, offering self fully and deeply to each other, and engaging together around a passionate call.

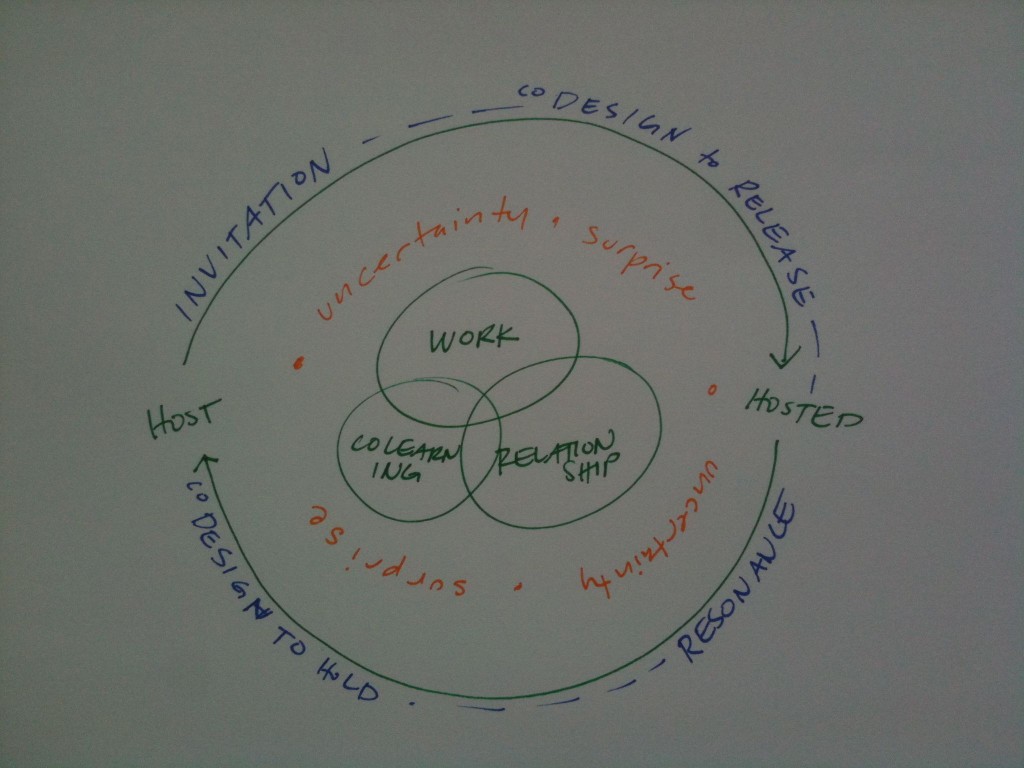

The distinction between host and hosted lies in the invitation, intention and the design. Being host means noticing and responding to a burning question, the passionate call to gather. Being hosted means responding to the resonance of that call. Being host means holding space (the physical and metaphysical) for the invitation and the gathering itself. Being host also means designing process to create the conditions to release holding the space to allow those hosted to co-create space. Hosting means intentionally letting go. Being hosted means following resonance and choosing where to place attention.

In the setting of an art of hosting gathering, the hosted have an opportunity to become hosts. The hosts also welcome being hosted. In this relationship, both the host and hosted are actively engaged in co-learning. Around the right question, this learning relationship takes place in connection to meaningful work.

Beyond the setting of an art of hosting offering, living the conundrum of being host and being hosted remains alive. To host well, I must be willing to be hosted. Willing to be hosted, I am open to surprise, willingly receiving what is offered.

Last week I recognized that I have been “holding” the art of hosting in Alberta for quite a long time with a couple of others – Marg and Hugh. It is hard to hold space – even with mates. It isn’t something that can even be held. It can only be.

The art of hosting is about co-creating space, and opening space. It isn’t something to hold long.

For wonderful details of the gathering, please see Tenneson Woolf’s harvest of the harvest of the harvest (photos, work/co-learning/relationship social movement piece on YouTube, blogs) here: http://web.me.com/tennesonwoolf/Tenneson_Woolf/Blog/Entries/2010/6/13_Harvest_-_Edmonton_Art_of_Hosting.html

Last night was the last night of my acting class, so it was “performance night.” We put our scenes on stage at the Citadel. Four things jump out at me as I reflect on the evening:

Last night was the last night of my acting class, so it was “performance night.” We put our scenes on stage at the Citadel. Four things jump out at me as I reflect on the evening: