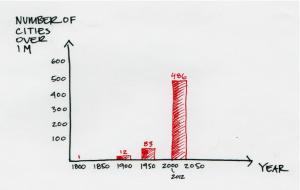

Over millennia, settlements and cities have started and thrived when and where the physical context was right, in an appropriate ‘habitat’. They have declined – and ended – when the physical habitat changed and the city didn’t or couldn’t adjust. A city may decline when the economy struggles, but the ultimate decline comes when there are physical limitations, such as no food or water.

A city and the citizens that make up the city rely on its physical habitat for its wellbeing. We rely fully on our physical inheritance and the decisions we make about what to do with our inheritance. Authors James Lovelock, Bill McKibben, Jared Diamond and Tim Flannery argue that as a species we have overextended ourselves; we have overused our inheritance. The result may be an over correction, as nature does with any species that reaches too high a population. It is not difficult to imagine this possibility given the rate that our population growth (overall and in cities) is accelerating.

Perhaps, unlike other earlier civilizations, we will cultivate our capacity to be conscious to what is happening around ourselves, to adapt, and survive. The stakes, though, are higher this time. This time the physical context we have to adjust to is planetary in scale, not local. The floundering of ancient civilizations did not mean the extinction of the human species.

In the 1960s, Lovelock first articulated Earth system science in what became Gaia theory. Seeing Earth as a living system, he defines our home as “not the house or the street or the nation where we live, but the Earth itself.”[1] Earth, or Gaia, is an emergent system on which climate and organisms are tightly coupled and evolve together.”[2] As things change, we adjust to them. Gaia does the same thing. We change her and she adjusts. Lovelock’s point is that she will self-regulate to survive. She doesn’t care if we survive or not, so if we wish to survive we need to heighten our abilities to adapt to the changing world. To do that, we need to heighten our abilities to notice our habitat. If cities are engines of innovation – and innovation is the engine of cities – our understanding of cities and habitat must advance.

Keeping an eye on our habitat, and responding appropriately, is a survival skill – one that we as a species can choose to hone. Earlier this week, I wrote that the development of cities is a survival skill. Perhaps this would be better stated this way: the evolution of cities is a survival skill. Ancient civilizations met their demise because of a lack of ability to adjust to changing life conditions: weather, food supply, environmental disasters or economic conditions. Our habitat can change for years over large geographies, such as the North American drought of the 1930s. Our habitat can change in hours, such as the forest fire that swept through the town of Slave Lake, Canada in the summer of 2011, destroying a third of the town. In the longer term, there is debate about whether we are on a trajectory of environmental demise as a result of climate change caused by human activity (which I do believe). But the debate is moot. Regardless of the cause, using any metric, it is hard to ignore that the world is no longer the place with which we have become familiar and that it is constantly changing.

The very nature of cities is changing. As cities grow, the very systems we put in place to organize ourselves, both consciously and unconsciously, are in flux. The physicality of cities (what we build) is changing. Cities grow and adapt to the needs of citizens over time. The economic systems we create also change constantly: sometimes dramatically. Our social systems are also changing. All of these systems emerge as a result of our work. As much as these systems and structures create who we are, at the same time we are creating them. We shape ourselves in relation to our environment, our physical, economic and social habitats.

So far, I have explored our economic life and it’s relationship in a physical habitat. In my next post I will add a third city habitat – the social habitat – and lay out the dynamic relationship of these three city habitats.