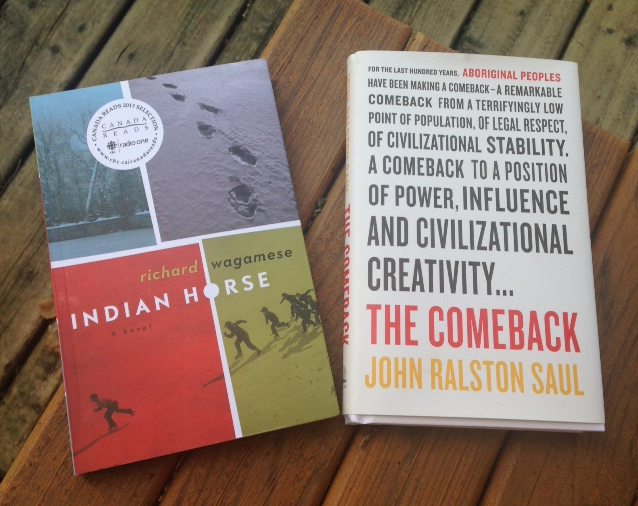

Noticing synchronicities, and responding to them, is one of the ways my deeper Soul-Self tells me who I am, and who I am longing to be. Today, the synchronicity is found in two Sauls: Richard Wagamese’s protagonist Saul Indian Horse, and writer John Ralston Saul.

Last year, I packed up and headed out on a wilderness quest. This year, I went again, as an apprentice guide, deepening into a pattern of being in better relationship with the land, and, more importantly, being in better relationship with myself. Following each experience, I found myself enjoying slow and relaxing time at the family cottage, beside a lake. I also found myself, upon both returns, reading the work of Richard Wagamese. This year, Indian Horse.

Saul Indian Horse is a young man reclaiming himself after the trials of losing family and a way of life, of residential school, and amazing hockey skill that brought him face-to-face with racism and hatred. His will to survive is tremendous, and in doing so he visits his land, and is able to tell his story.

I’d close my eyes and feel it. The land was a presence. It had eyes, and I was being scrutinized. But I never felt out of place. I couldn’t take it. I couldn’t run the risk of someone knowing me, because I don’t take the risk of knowing myself. I understood then, as fully as I ever understood anything.Saul tells the story of what it takes to be honest with oneself, to truly know oneself. Wagamese tells a story of the stories my country is telling and hearing, of the betrayals of Aboriginal peoples by non-Aboriginal people in residential schools through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the inherent racism that surrounds the schools and non-Aboriginal views of Aboriginal people. We are all starting to look the truth in the eye.

Saul’s exchange with his great-grandfather is as insightful for him as it is for my country:

‘The journey you make is good.’ ‘What am I to learn here?’ He swept his arm to take in the lake, the shore, and the cliff behind us. ‘You’ve come to learn to carry this place within you. This place of beginnings and endings.’My country is in transition, and the nature of that transition is articulated by another Saul, John Ralston Saul, in The Comeback. Saul charts the formation of our country, one where newcomers arrived and were treated as guests, with the expectation that hospitality would be returned in some way. Then oral agreements, treaties were signed, full of the notion of reciprocity brought by the First Nations way of being and agreed upon by the Crown and its representatives.

Balance and reciprocity. Much of what works in our society is based on balance and reciprocity. Transfer payments. Health care. The only group not to benefit is the group that actually installed this concept of governance. Again, for each of us as citizens it is a matter of being honest with ourselves. We must act to ensure that balance and reciprocity are applied in indigenous relations, as agreed to in the treaties.The notion of balance and reciprocity, a founding pillar of our country, originates not from European ‘founders’ of Canada, but from First Nations. In return, we ensure a lack of balance and reciprocity toward these same people, and even choose to destroy these people. This is a betrayal that has lasted for centuries now.

Saul wonders if the crisis we face in Canada is not in the Aboriginal world, as we think, but in ourselves.

But is the more profound crisis not in the non-Aboriginal world? If not, why would we find it so difficult to listen – to listen seriously – to the points of view coming from the founding pillar of our civilization? Are we so insecure? So frightened to absorb views that after all have been central to Canada’s establishment and survival? Or is it a lack of sensibility? An emotional wall constructed unconsciously to protect ourselves from the reality of this place? Or a simple lack of consciousness? Or all of the above?And the words of Grand Chief David Courchene in 1971, as cited by Saul:

We ask you for assistance for the good of all Canada and as a moral obligation resulting from injustice in the past, but such assistance must be based upon this understanding. If this can be done, we shall continue to commit ourselves to a spirit of cooperation. Only thus can hope be bright that there might come a tomorrow when you, the descendants of the settlers of our lands, can say to the world, Look, we came and were welcomed, and then we wrought much despair, but we are also men of honour and integrity and we set to work in cooperation, we listened and we learned, we gave our support, and today we live in harmony with the first people of this land who now call us, brothers. We hope that tomorrow will come.These Saul stories are the stories of my Soul, my desire to draw on the Indigenous nature of me, the land I call home, and the Indigenous people who were here before my descendants. These Saul stories point me to a new place for me and my work as a non-Aboriginal Canadian, to restore the principles of balance and reciprocity that are the foundational pillars of Canada.

I will say it, Grand Chief David Courchene, for myself:

We came and were welcomed, and then we wrought much despair. I am a person of honour and integrity and I set to work in cooperation. I have listened and I have learned and give my support. I desire to wish to live in harmony with the first people of this land, my brothers and sisters.

Aho.

I have spoken.

_____

Sources:

John Ralston Saul, The Comeback (Toronto: Penguin, 2014)

Richard Wagamese, Indian Horse (Madeira Park: Douglas and McIntyre, 2012)