In yesterday’s post, I reached the conclusion that the quality of the relationship between our economic life and our social and physical habitats dictates our ability to generate cities that meet our economic, social and physical needs. We create cities for the purpose of our individual and collective growth. We create them to support our evolution.

Feedback Activity

Consider this simplified illustration of the city dynamic (Figure A), where the red center is our economic life, and green and blue are our social and physical habitats. (For more information on the relationships between these three elements, please visit Cities need quality feedback.) The feedback between our economic life and our habitat is the information that flows back and forth. Feedback between our social and economic life is critical, as is feedback between our physical habitat and our economic life. The more activity between these spheres, the more responsive a city is to the needs of its inhabitants. For example, the illustration of activity in Figure B is less healthy than that of activity in Figure C in that it offers less feedback. Less feedback may mean lower adaptation of our economic life to meet the demands of our changing social and physical habitat.

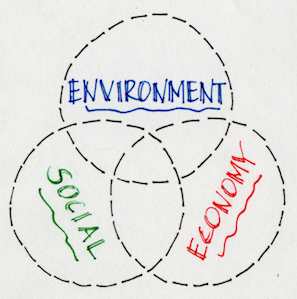

This perspective of the city’s habitats nests the physical, social and economic worlds. This understanding builds on the lineage of our current understanding of sustainable development, rooted in the World Commission on Environment and Development’s 1987 report, Our Common Future, often referred to as the Brundtland Commission. (Two links that might be of interest: the story, the report itself.) The inheritance offered by this report is the insertion, into our collective planetary consciousness, of the relationship between our physical, social and economic lives. This is now, rather conventionally, shown graphically as a Venn diagram (Figure D).

The dynamic of the city habitat as I have described it here and in previous posts rearranges our understanding of sustainable development. Looking at cities from an evolutionary perspective, our physical habitat holds everything. Within that we have evolved socially to create opportunities for new work, a feature of our economic life that generates cities, and in turn recreates our physical habitat. The city dynamic consists of endless feedback loops, going in all directions all at once (Figure C). Each sphere is critical, but with distinct roles to play. Unlike the Venn Diagram, each element is never fully on its own. It is all interwoven and interrelated.

The nature of these relationships is such that the healthier the city, the more interactions across and within the layers. Remember these three patterns about how new work (innovation in our economic life) works (see earlier posts for more on this – development of cities, and our work creates cities):

- The development of new work means new ideas in response to life conditions.

- The expansion of new work means implementation in response to life conditions.

- The link between development and expansion of new work is habitat: life conditions.

These principles and how they behave give us clues about how to organize ourselves, such that we tune into, and be in tune with our habitat. The interaction between these spheres is where the future lies for our cities. How we organize our cities to gain this feedback and respond to it is a necessary survival skill. With feedback, and appropriate responses to that feedback, we can adjust our path; without we can not.

Feedback and Adjustment

We need to approach our city systems in ways that allow for feedback and adjustment. Brian Robertson, and his work on holacracy, describes this as dynamic steering, where a system receives regular, real feedback and immediately adjusts. Imagine the system is you riding a bicycle. As you move along, you start to tip, you adjust. You see a pothole head, you adjust. You see what is coming and you adjust, but the truth is you never know ahead of time what will come and what the appropriate adjustment will be. Yet you are able to do it.

Most systems we are familiar with, such as organizations, operate in predict-and-control mode, where we anticipate what is going to happen and make the adjustment prior to even seeing if the event unfolds as expected. We also make adjustments after events, assuming that future events will be the same and will need the same reaction. Predict-and-control mode does not allow for appropriate responses to life conditions because it allows only minimal feedback between the habitats of the city. Imagine riding a bicycle with arms out stiff in front of you; it doesn’t allow you to be responsive. We need cities to be responsive.

In our cities, as when we ride a bicycle, our ability to keep our eyes on where we are going matters. Our ability to notice when we have moved off track matters. Our ability to choose to get back on track matters. Our ability to do the work at hand matters. Our very approach to our work matters. It also means that we have to have a bicycle that is in good working condition and does what we ask it to do.

In today’s cities, with today’s challenges, we have an opportunity to be explicit about the cities we are creating and how they shape us in return. We have an opportunity to integrate our economic, social and physical worlds in such a way that will allow us to respond to the changing conditions in our world. Debating climate change is moot when the world is changing in so many ways. It is a distraction from the true work at hand – learning how to dynamically steer our cities into the future that allows life to flourish. Learning to be even more adaptable than we have been is key. It means being open to feedback and willing to take action – at any and all scales. There is lots of work for us to do.

The next post will touch on the scales at which we work in our cities. Does the scale we work at matter?